You Know What Else Kills Birth Rates? Being in a Region That's Falling Behind

A new study from South Korea suggests the growing distance between places is a demographic problem, not just an economic one.

In 2023, South Korea recorded a total fertility rate of 0.72 children per woman, the lowest figure any country has produced in the modern era of demographic measurement. Not Japan. Not Italy. Not any of the famously low-fertility societies of Southern or Eastern Europe. Korea.

The speed of the collapse is what makes it extraordinary. In the early 1960s, Korean women averaged nearly six children each. By 1983, the rate had dropped below the replacement level of 2.1. That was fast but not historically unusual; many developing countries compressed their fertility transitions into a few decades. What happened next was unusual. The rate kept falling. It never rebounded. After 2010 the decline accelerated, and in 2018 the TFR slipped below one child per woman for the first time in recorded history. Five years later: 0.72. Maternity wards are closing. Elementary schools are consolidating. The government projects the population, currently around 52 million, could fall below 40 million by 2060 without a dramatic reversal.

Now consider the economic trajectory alongside the demographic one. In 1960, Korea’s GDP stood at roughly $4 billion. By 2023, it had surpassed $1.7 trillion. The country’s Human Development Index ranks among the highest in the world. Korea produces the planet’s most advanced semiconductors, builds globally competitive automobiles, and exports film, music and television that dominate international markets. A Korean company probably manufactured the phone in your pocket or the screen you are reading this on.

By every conventional measure of national prosperity, Korea is a triumph. By the single most consequential measure of demographic sustainability, it is in crisis. GDP growth of roughly 42,000 per cent over six decades. A fertility rate of 0.72.

How do these two facts coexist? A recent study by Kyungjae Lee and Seongwoo Lee (2026), published in Population, Space and Place, offers an interesting answer. Not in the choices of individual women, and not in national economic aggregates, but in the widening economic distance between Korean regions. The relationship between regional inequality and fertility turns out to be subtler than the standard accounts suggest, and the subtlety matters a great deal.

The usual suspects

The standard story about Korea’s fertility collapse is not wrong. It is incomplete.

Korea’s labour market has become increasingly split between protected regular employment and precarious contract work, with younger cohorts disproportionately stuck in the latter. Stable jobs facilitate family formation; unstable ones suppress it. In the Seoul metropolitan area, apartment prices have reached levels that make purchasing a home, long considered a cultural prerequisite for marriage, feel like an impossible aspiration for young couples. And women who want careers face enormous pressure to sacrifice childbearing, because the institutions and norms that might allow them to do both (genuinely shared parenting, flexible work arrangements, affordable childcare) remain underdeveloped.

Hwang (2023) demonstrates that fertility decline in Korea has occurred broadly across educational and employment groups. Not just among the highly educated. Not just among the precariously employed. Across the board. Decomposition analyses show the decline is driven primarily by within-group changes: women at every level of education and in every employment category are having fewer children. If the collapse were really about more women attending university or entering the labour force, the decline should concentrate among those groups. It doesn’t.

Something structural is operating above the level of personal characteristics, reshaping the conditions under which families form regardless of who the individuals are. The usual suspects have been correctly identified. But they are not the ringleaders.

So what is?

What the maps reveal

Lee and Lee’s answer begins with geography. Literally, with maps.

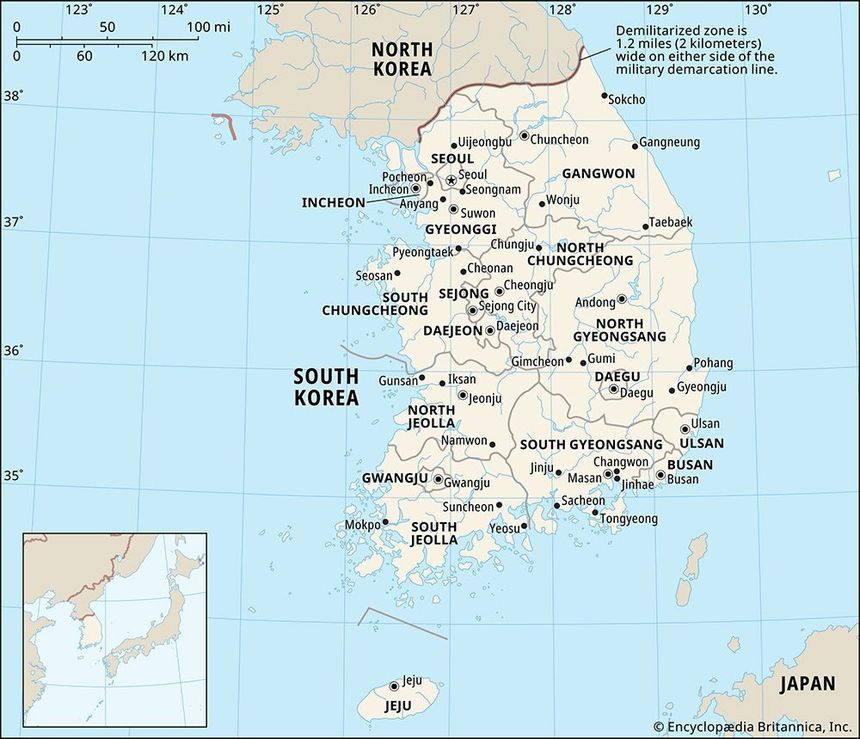

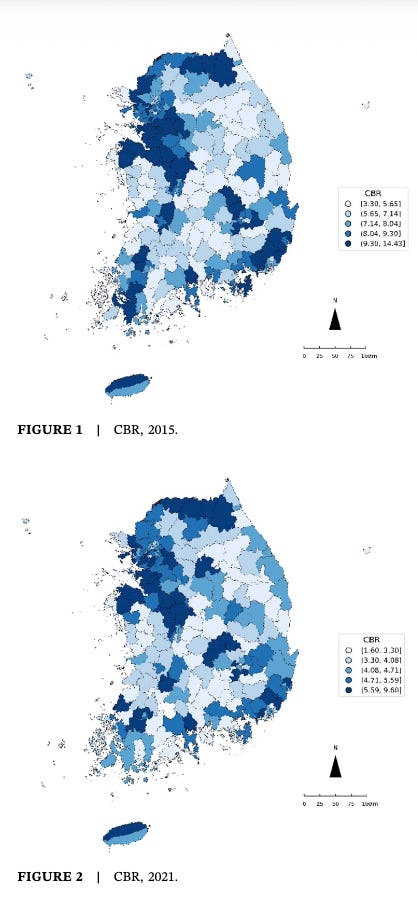

Compare the spatial distribution of crude birth rates across Korea’s 229 districts in 2015 and 2021. The first pattern is straightforward: the CBR declined substantially in nearly every district over the six-year period. This is not a story of births migrating from one region to another. The entire distribution shifted downward. Fertility fell almost everywhere.

The second pattern is the one that matters. The relative economic positioning of districts shifted simultaneously. Lee and Lee measure regional economic disparity using Yitzhaki’s relative deprivation index, which calculates each district’s position by averaging the gap between its gross regional domestic product and the GRDP of every district above it. The result is a unique deprivation score for each of the 229 districts. Between 2015 and 2021, relative deprivation increased across the distribution. Districts that were already disadvantaged fell further behind. The economic hierarchy steepened.

Fertility decline and widening regional disparity unfolded in tandem, across the same space, over the same years. That visual correspondence is descriptive only; it does not establish causation. But it is suggestive enough to warrant digging deeper.

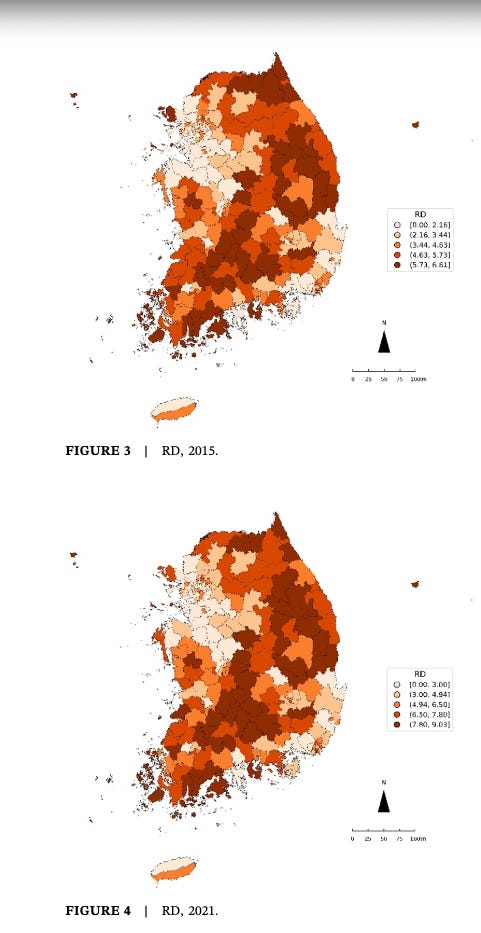

The backstory of Korea’s regional inequality makes the pattern easier to understand. In the 1960s and 1970s, industrial cities along the Seoul-Busan corridor and the southeastern coast developed concurrently. Regional disparities were not particularly pronounced. But since the 2000s, population and industry have concentrated relentlessly in the Seoul Metropolitan Area: Seoul, Incheon and Gyeonggi-do. Today, more than half of Korea’s population and GDP are packed into the SMA. High-skill employment clusters in the capital region. Non-metropolitan areas experience what the academic literature calls “weakening industrial bases” and what residents experience as the slow disappearance of jobs, young people and civic life. Entire towns in the rural south now have more residents over 65 than under 40.

The SMA is not, however, a fertility-friendly environment. It faces crushing housing costs, intense competition for scarce school and childcare places, and a private education arms race that makes raising children in Seoul extraordinarily expensive. Non-SMA regions have lower living costs, but the outflow of young adults has hollowed out their demographic foundations.

Both sides of the divide face fertility-suppressing pressures, for different reasons. Lee and Lee’s argument is that the growing distance between these two worlds is itself a mechanism. It is not simply that Seoul is expensive or that provincial cities are declining. It is that the gap between them has widened into a spatial hierarchy that constrains family formation regardless of where you stand within it. The standard expectation (get rich, have kids again, the so-called J-curve hypothesis of Myrskylä) fails in Korea because national prosperity has been distributed so unevenly across space that aggregate growth coexists with intensifying regional deprivation. When national wealth concentrates in one place, neither the rich region nor the poor one produces enough children.

People do not just respond to what they have. They respond to what they have relative to what they see others having. Regions positioned differently within a national economic hierarchy face different constraints on fertility, even when the people living in those regions share similar personal characteristics.

That is the theory. Here is how Lee and Lee tested it, and what they found.

The evidence, and its surprise

The study employed two complementary approaches: a spatial panel analysis of all 229 Korean districts from 2015 to 2021, and a multilevel model of 86,980 married women aged 19 to 49 drawn from the 2020 Population and Housing Census.

The methods matter here. Birth rates in neighbouring districts are not independent. Moran’s I tests confirm statistically significant spatial clustering of fertility rates in every year of the study period, all at the 1 per cent level. Ignoring this spatial dependence biases standard regression estimates. The spatial panel models account for it. Two-way fixed effects remove time-invariant regional characteristics and year-specific shocks common to all regions, isolating the effect of changes in relative deprivation on changes in birth rates. The multilevel model, meanwhile, nests individual women within their districts, separating compositional effects (who the woman is) from contextual effects (where the woman lives). Together, the two approaches let the authors check whether a pattern visible in regional aggregates also shows up in individual women’s childbearing behaviour.

The regional results are clear and consistent. Across all three spatial model specifications, the coefficient on relative deprivation is negative and statistically significant at the 1 per cent level. In substantive terms, a 1 per cent increase in a district’s relative deprivation is associated with a decrease of approximately 0.013 in the crude birth rate per thousand population. Relative deprivation increased substantially and broadly across districts over the study period; aggregated across 229 districts and six years, the cumulative drag on fertility is considerable.

Among the control variables, two are worth pausing on. Regional economic output (GRDP) carries a significant negative coefficient. That is: economic growth, as it has actually occurred in Korea, concentrated in the metropolitan core and accompanied by rising costs, is associated with lower fertility, not higher. The marriage rate, meanwhile, is strongly positive, reflecting the near-universal norm in Korea that childbirth occurs within formal unions. Housing costs and population density are both negative, as expected.

Now for the surprise. When Lee and Lee turn to the individual-level multilevel models, the first result seems to contradict everything the spatial panel analysis just established.

In Model 1, which includes the level of relative deprivation as a regional variable, the coefficient is positive. Economically disadvantaged regions had somewhat higher fertility in the 2020 cross-section. If regional deprivation suppresses fertility, why do more deprived regions have more births per woman?

Tempting, but wrong. That positive association reflects level differences, a snapshot. Some lower-income regions in Korea have historically maintained somewhat higher fertility, often linked to more conservative family norms and lower costs of living. But a snapshot is not a trajectory. When the authors move to Model 2 and examine the growth rate of relative deprivation, the change from 2019 to 2020, the coefficient flips sharply negative (−0.56, significant at the 1 per cent level). Districts where the gap widened saw married women bear fewer children, even after controlling for age, education, homeownership, housing type, and employment status of both the woman and her spouse.

It is not the level of disadvantage that suppresses childbearing. It is the widening of the gap.

That distinction matters enormously. A region can have relatively low economic output and still sustain reasonable fertility, so long as its position in the hierarchy is not deteriorating. But when the distance to the prosperous core grows, fertility falls.

The convergence of these results across both levels of analysis is what makes the finding hard to dismiss. The negative association between widening regional inequality and fertility is not an artefact of aggregation. It appears in district-level panel data, and it appears in the childbearing behaviour of individual married women. Both point the same direction.

What this means for Korea and beyond

Lee and Lee’s findings suggest pronatalist interventions may be considerably more effective when paired with strategies that keep young people in places outside the capital. The significant positive coefficients on the share of young adults and women in the spatial models reinforce this: regions that retain these demographic groups maintain stronger fertility potential. The question, and it is genuinely difficult, is how.

Korea is an extreme case, but the underlying dynamics are not unique. Japan’s economy and population have been concentrating in the Tokyo metropolitan area for decades while rural prefectures empty out, and Japanese fertility has followed a strikingly similar downward path. Italy’s Mezzogiorno-North divide tells a version of the same story. The mechanism Lee and Lee identify, spatial relative deprivation operating as a contextual constraint on family formation, follows from the logic of uneven development itself.

I should be candid about what the study does not yet settle. It demonstrates a robust negative association between widening regional disparities and fertility, but it does not fully trace the causal pathways. Cultural norms, local policy interventions and migration decisions all likely mediate the relationship in ways the data cannot yet model. The two-way fixed effects and extensive controls mitigate omitted variable bias, but they cannot eliminate it.

The core finding, though, reframes the conversation about demographic decline. Lee and Lee argue that regional economic disparity is the structural force operating above individual characteristics, and their evidence, drawn from both district-level panels and the childbearing behavior of nearly 87,000 women, is consistent at every level of analysis.