Yes, I am a pro-natalist

An Interruption To Our Regularly Scheduled Programming

Ann Ledbetter recently wrote a piece arguing that the pronatalist movement doesn’t care about mothers. She describes women experiencing panic attacks when they return to hospitals where they had traumatic births. She cites research showing unplanned cesareans reduce subsequent fertility by 28-34%. She points out that Richard Hanania’s “ideal fertility rate of 6.5” translates, for a third of American women, into multiple major abdominal surgeries with escalating risks.

I agree with almost all of her substance. It’s exactly the kind of quality of life/systems-level analysis I’ve been trying to bring to this discourse.

And then I (or more specifically pronatalists) get lumped in with Hanania and Musk.

More than likely, she isn’t really aware of what pronatalism is in real life or aware of anything I written. I have a strong feeling she would like the stories of Minamiminowa in Japan, South Tyrol in Italy, or Yeonggwang in Korea. I also like to think she would be surprised on how much pronatalist academic research focus on the quality of life issue. None of it required Musk to tweet about population collapse or Hanania to calculate optimal fertility rates.

Still, lumping me in with Musk, Hanania, etc? I’m a bit miffed of being associated with people whose actual practices contradict both real world research and I personally advocate for. I’m even more miffed about relitigating terminology when there’s more interesting things to discuss.

So here’s my attempt to redirect to conversation toward towards said interesting things, and answer some questions in the meantime.

The Conversation So Far

Ivana Greco kicked this off by explaining why she’s not a pronatalist. Heavy-handed rhetoric alienates women. National spending in Hungary and Korea hasn’t moved the needle. American fertility isn’t broken yet. The label carries baggage she doesn’t want.

Lyman Stone pushed back: if you want more babies, say so. “Pro-family” is evasive. Refusing to name what you’re for cedes ground to people who are happened to be against.

Patrick T Brown shares some of Greco’s concerns (Musk’s surrogacy arrangements, eugenicist rhetoric at conferences, proposals that pressure women without asking men to change) but thinks Stone is asking the right question.

Now Ledbetter has sharpened Greco’s critique from the perspective of someone who actually delivers babies. Her point isn’t about rhetoric or coalition management. It’s about what happens in exam rooms and operating theaters. A movement that talks about “ideal fertility rates of 6.5” without acknowledging what that means for women’s health isn’t serious.

Meanwhile, a genre of lazy commentary positions itself above the fray: everyone’s shoehorning their priors, nothing works, prosperity itself is the problem, wait for artificial wombs.

The questions below are my attempt to move past the terminology fight toward what the evidence actually shows.

Part I: The Terminology Fight

Q1: Should we just say “pronatalist”?

Yes. Stone is right about this.

“Pro-family” is a flag of convenience. Conservatives use it to mean traditional marriage; progressives use it to mean paid leave. The term means nothing.

On that note, what makes you think bad actors won’t just co-opt the new term? Let’s save time.

I’m a pronatalist. More babies. Specifically: helping people have the children they already want. Removing barriers, reducing risk.

And before people go conservative policy on me, Aria Schrecker pointed out, liberal countries have more children than conservative ones. So things are not as clear cut as people pretend.

Q2: Greco, Brown, and Ledbetter all hesitate to embrace the label. Are their concerns trivial?

No. They’re identifying real problems.

Greco worries that heavy-handed rhetoric will politicize fertility and drive liberal women away. The messenger matters, and the movement’s worst voices are often its loudest.

Brown worries about capture by bad actors: Musk’s surrogacy-and-NDA arrangements, men seeking multiple partners for “civilizational” reasons, proposals that pressure women without asking men to step up.

Ledbetter goes further: when Hanania proposes 4-8 children per woman, is he proposing multiple major abdominal surgeries for a third of American women? Would he care about their health? We know he doesn’t care about economic losers. Hanania treats this as a detail, but as much as he would hand wave it away, it doesn’t change the fact that traumatic births reduce subsequent fertility.

Part II: The Measurement Problem

Q3: Greco points to Hungary and Korea as evidence that national spending doesn’t move fertility. Is she right?

Wrong on the spending, right on the variation.

Hungary’s fertility rose from 1.25 in 2012 to 1.52 in 2022 after implementing marriage bonuses, housing programs, and cash benefits. Evaluating it by post-invasion fertility (during Europe’s energy crisis and austerity) is like weighing someone after hospitalization.

Lyman Stone’s research directly addresses the “cash doesn’t work” claim. His analysis of 43 studies covering 58 policies (yes,hat is a lot) shows clear correlation between benefit generosity and fertility increases. The 17 countries implementing major policies since 2000 saw increases of 0.09-0.18 births per woman, persisting 10+ years.

Mongolia increased fertility from 2.0 to nearly 3.0 after implementing cash benefits. Japan’s 2010 reforms prevented collapse from 1.4 to 0.8. Czechia vs. Slovakia provides a natural experiment: after their split, Czechia maintained steadier support while Slovakia cut aggressively. Result: 0.31 swing toward Czechia.

But here’s what Greco’s skepticism correctly identifies: national averages hide enormous local variation. Japan has cities like Akashi and Nagareyama with much higher rates. Korea’s Yeonggwang County achieves 1.71 (double the national 0.75) while Busan’s Jung District hits 0.38.

Treating national averages as “proof nothing works” ignores what actually varies: local policy choices and sustained commitment.

Q4: Everyone uses Total Fertility Rate. Is that the right metric?

No. And the problems run deeper than most people recognize.

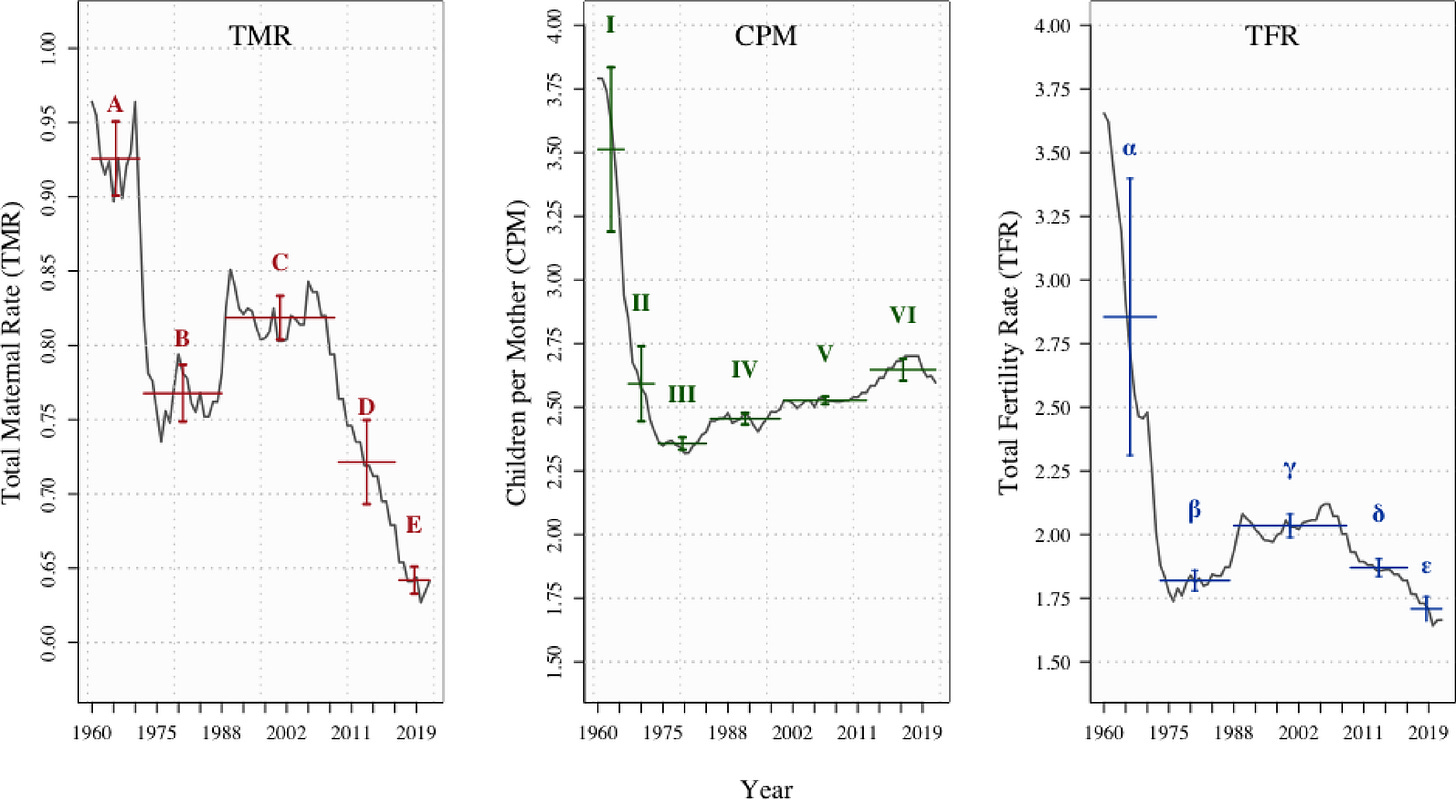

TFR conflates two independent dynamics: how many women become mothers at all (Total Motherhood Rate) and how many children mothers have (Children Per Mother). Stephen J Shaw research across 314 million mothers found these show near zero correlation. They respond to different forces and need different interventions. Using TFR alone discards half the diagnostic information.

Consider: In 1980, 76.1% of American women became mothers and averaged 2.39 children each (TFR 1.82). By 2016, only 69.4% became mothers but averaged 2.63 children (same TFR).

Greco says American fertility “isn’t broken” because cohort TFR remains near 1.95. The decomposition tells a different story. France achieves higher fertility by helping more women become mothers. The US achieves similar numbers through concentration.

Edward Deming was scathing about management by single numerical targets. You cannot improve what you cannot measure, but measuring the wrong things produces perverse outcomes. TFR invites this error.

Policymakers optimize for the headline number while ignoring underlying dynamics. A TFR increase driven by economic winners having more children while everyone else is excluded isn’t success. It’s just going to give us wrong ideas on what is the problem and how to deal with the problem.

Track TMR and CPM separately should be the first, but not only, step that people should take next.

Q5: What’s driving the decline in motherhood specifically?

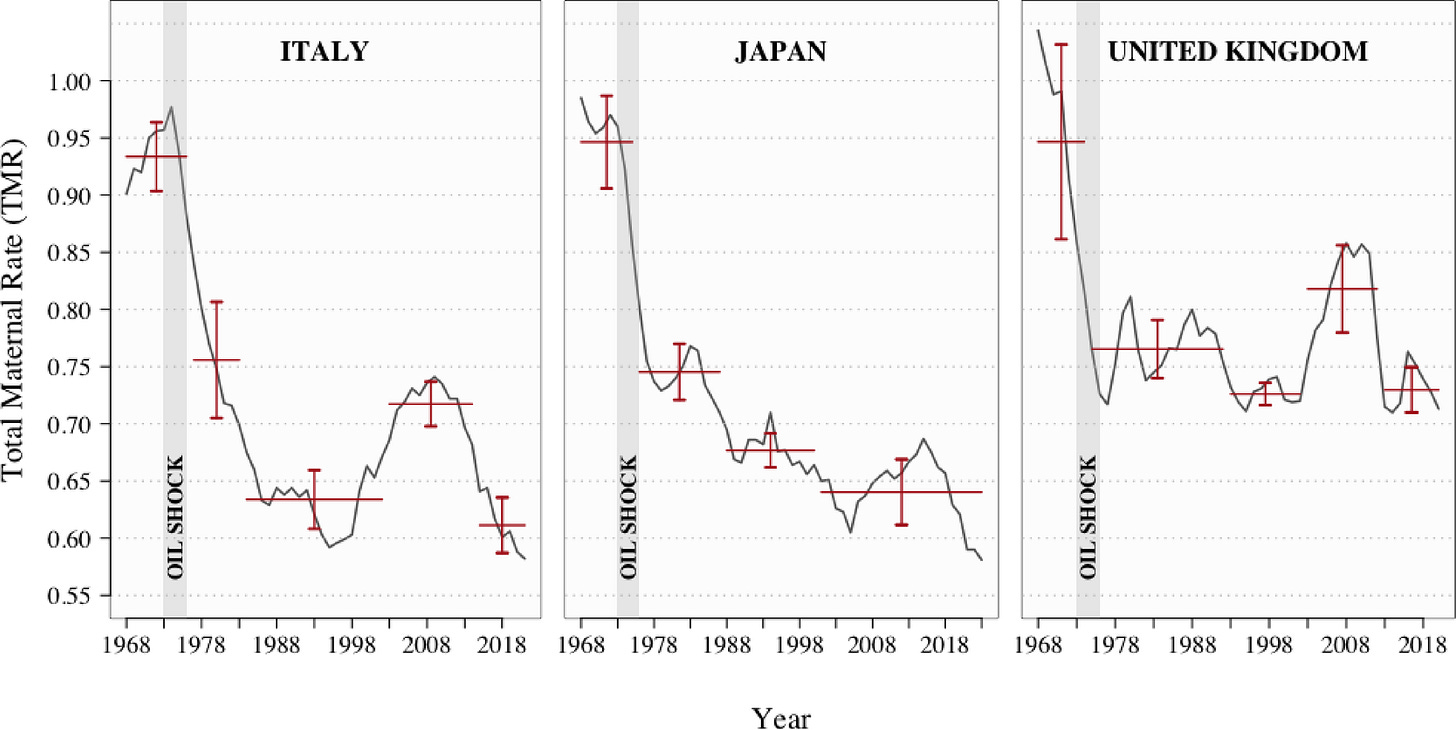

The biggest reason is economic scarring of young people, especially young men. Every recession collapses TMR and marriage rates. If they fail to recover, damage compounds when the next shock hits.

TMR tracks marriage, which tracks male economic stability, which tracks the shocks we keep inflicting on entry-level labor markets. Researchers tracked 400 regions in Germany across 13 years and found job destruction reduced fertility 38% more than job creation increased it. When factories closed, birth rates plummeted. When new positions opened, fertility barely budged.

The 2008 financial crisis didn’t cause a temporary dip. TMR dropped 6.7 percentage points and never recovered. Men who experience employment instability in their twenties need fifteen years of stable employment to match their peers’ marriage prospects.

Japan shows the same pattern. Women in non-regular employment express half the fertility intentions of regular employees. Precarity makes both ambition and motherhood impossible.

The mechanism is repeating now. The 20-24 unemployment rate jumped from 5.5% to 8.2% in eighteen months after Fed tightening. We’re creating the next generation of 45-year-olds who never recovered.

Q6: Ledbetter argues that birth experiences shape subsequent fertility. Is that measurable?

Yes, and the effect is large. This is one of the most important feedback loops the standard discourse ignores.

Haley Wilbert’s study used Army health claims and medical records to isolate the effect of cesarean delivery on future childbearing. Among women with unplanned cesareans, the probability of subsequent childbirth within four years dropped by 28% to 34%. The mechanism runs through both physical and psychological pathways: increased hospital readmission and mental health visits following unplanned procedures.

Deming insisted that 94% of problems are attributable to the system, not to individuals. The maternity care crisis isn’t about bad doctors or weak mothers. It’s about a system optimized for defensive medicine, liability avoidance, and throughput. When 32% of births are cesareans and only 16% of counties offer VBAC, that’s system output.

Blaming women for being “too scared” after traumatic births misses the point: what about this system produces traumatic births?

Part III: The Systems Framework

Q7: What framework should guide fertility policy?

I don’t share the theological commitments that animate some of Stone’s work, or the Catholic social teaching behind Brown’s. My framework comes from a different tradition: Deming’s quality management, Beer’s organizational cybernetics, Juran’s quality trilogy. Measure the right things. Break down silos. Constancy of purpose. Build systems with enough redundancy to absorb shocks.

One of my favorite useful tool from this world to think about things is Stafford Beer’s The Purpose of a System Is What It Does (POSIWID). Not what the mission statement says, not what designers intended, but what the system actually produces. If a maternity care system consistently produces traumatic birth experiences, that’s what the system does. If online discourse produces viral threads and personal brands but no policy changes, that’s what the discourse is for.

Jospeh Juran distinguished three phases: quality planning (designing processes capable of meeting goals), quality control (monitoring and correcting deviations), and quality improvement (systematically raising baseline performance). Most government fertility policy skips planning and improvement entirely, leaving only reactive control: throwing money at symptoms without understanding the system that produces them.

Korea has spent billions “addressing low fertility” without thinking about how to design a system capable of producing higher fertility under real-world conditions. No one planned the current system; it accreted. And because there’s no systematic improvement process, the same failure modes persist indefinitely.

What distinguishes successful places is what Deming called constancy of purpose: sustained commitment to improvement over decades rather than flavor-of-the-month initiatives. Systems change slowly. Leaders must persist.

Q8: What makes family formation feel so fragile now?

The compensatory pathways have been stripped out. The system has lost redundancy.

A “simple complex system” is simple enough to be prone to cascades but complex enough that you can’t predict what will fail. Family formation has become this. The pathways that used to compensate for each other are gone:

Extended family nearby? Increasingly rare.

Single income sufficient for housing? Gone in most metros.

Flexible work permitting engaged parenting? Until 2020, almost nonexistent.

Stable employment in your twenties? Destroyed every time the Fed tightens, let alone economic shocks since the 70s oil crisis.

Supportive birth experience? For many women, no longer available.

Each failure stresses the remaining paths. Each cohort has fewer options.

Taking a page from cybernetics is Ashby’s Law, that a system’s regulatory capacity must match the variety of disturbances it faces. When the environment grows more complex but organizational capacity doesn’t keep pace, failure is inevitable. Family formation now faces more variety than ever (dual careers, geographic mobility, housing cost volatility, gig employment, delayed partnership formation) but with social and economic systems that would have supported family formation collapsed.

One-size-fits-all national policies lack the requisite variety to address diverse local conditions. The way forward isn’t one policy that solves everything. It’s restoring this “socioeconomic” redundancy: multiple pathways to stable employment, housing, childcare, and birth experiences that don’t traumatize women out of subsequent pregnancies.

Q9: If “family policy” is too narrow, what actually counts?

Everything that shapes the barriers. The silos between policy domains obscure that the system is interconnected.

The silos aren’t just administrative inconvenience. They break feedback loops. The people making monetary policy decisions don’t receive information about fertility effects fifteen years later. The people setting childcare ratios don’t see the families priced out. Decision-makers never learn the consequences of their decisions because the information arrives too late or flows to different people.

Housing is family policy. Rising values mean rising rents, fewer first-time buyers, lower fertility.

Work flexibility is family policy. Norway’s 2020 lockdown gave rigid-job workers schedule control for the first time. Births increased 10%, with the effect 152% stronger among workers who’d never had flexibility. The 40-hour fixed-schedule workweek actively prevents engaged parenting.

Maternity care is family policy. The cesarean-to-subsequent-fertility feedback loop is a 28-34% effect.

Energy prices and monetary policy are family policy. Energy shocks collapse fertility worldwide. Fed tightening scars young workers with fifteen-year echoes.

The system is already shaping outcomes. The question is whether we’re honest about what we’re doing.

Part IV: What That Work

Q10: Where has pronatalism actually worked?

In places where systems produce the outcomes they claim to want, through sustained implementation at multiple levels.

National policy sets the floor. Stone’s research shows Japan’s 2010 interventions prevented fertility from collapsing to 0.8; Mongolia’s cash benefits produced a 50% increase; Hungary rose from 1.25 to 1.52. The “financial incentives don’t work” consensus is wrong.

But national policy alone doesn’t explain the variation. The places achieving outlier results share common features: sustained local commitment, operational focus, barrier removal across multiple domains.

Japan: National Floor Plus Municipal Excellence

Akashi (1.65 fertility): Former Mayor Fusaho Izumi cut public works spending, doubled childcare allocations, and sustained it through a decade of opposition. Free medical care to age 18, free school lunches, free nursery for families with two or more children. Cleverest intervention: free diapers delivered by midwives, combining material support with professional outreach. Population grew ten consecutive years.

Nagareyama: Station-based childcare handles pickup and dropoff, letting parents commute to Tokyo. 29% of elementary families in the city have three or more children. Whether Nagareyama’s policies caused this directly, or just attracted families who already wanted more kids, or whether concentrating young families together creates its own momentum, I’d genuinely love to have the funding to research it.

Minamiminowa Village (1.76 fertility): Former mayor Karaki Kazunao persisted despite criticism, creating systematic childcare reductions, free healthcare through high school, participatory governance. With 73.3% transplants, the village developed “appropriately weak ties,” connections that provide support without overbearing pressure.

Korea: Yeonggwang County

Yeonggwang County (영광군) hit a total fertility rate of 1.71 in 2024 (more than double Korea’s national average of 0.75) and has held the nation’s top spot for six consecutive years. There’s no single magic subsidy here. Former Mayor Kang Jong-man credited the “connectivity” (연계성) of policies: youth employment support linked to marriage support linked to birth support linked to childcare.

The county runs about 80 programs covering the whole lifecycle. Birth payments get more generous with each child: 5 million won for the first, 12 million for the second, 30 million for the third through fifth, and 35 million for the sixth onward. There’s also a 500-million-won marriage incentive, a 3-million-won allowance for fathers taking paternity leave, and infertility treatment subsidies up to 1.5 million won.

But the money alone doesn’t explain it. Yeonggwang ties fertility support to jobs and housing. The county set up the nation’s first 10-billion-won Youth Development Fund in 2021, built youth housing at “Neulpum Village,” and partnered with LH to supply 300 public rental units for newlyweds. Stable jobs at the Hanbit Nuclear Power Plant and a growing e-mobility cluster mean young families can actually stay.

The numbers back it up: marriages rose 40% year-over-year in 2024, and the county’s population grew by 1,693 residents, with notable gains among young people and infants.

South Tyrol, Italy

Phoebe Arslanagić-Little did a neat article on South Tyrol, a provincial area in Italy. Parents receive 200 euros monthly per child until age three, plus an annual 1,900 euros from the Italian government. All newborns registered in the province come with a 'Ben Arrivato Bebé' package including baby items, books, a voucher for more books, and an 'Euregio Family Pass' for discounted public transport. The Family+ card offers shop discounts for parents with three or more children. The 'Casa Bimbo' system provides flexible childcare through local teachers operating home-based nurseries. That is not what made it successful, but the fact that South Tyrol been working at improving quality for families over forty years of sustained commitment, not one-off bonuses cut during as soon politics demanded it. Result: 1.64 fertility with 73% female employment, 37% above Italy’s national rate.

As one demographer put it: “Nobody plans to have children on the basis of one-off policies.”

The Pattern

What these places share isn’t a specific policy mix. It’s constancy of purpose sustained through political opposition. The pattern is scale-invariant: sustained commitment, barrier removal across domains, feedback from families to decision-makers, requisite variety in policy tools.

Q11: Does effective pronatalism require massive spending?

No. Some of the highest-impact interventions cost nothing. They remove barriers the government created.

Peter Foreshaw Brookes at the Centre for Family and Education compiled zero-cost family support measures for the UK:

Childcare ratios. The UK has Europe’s strictest staff-to-child requirements. Denmark, Spain, and Sweden have no mandates. Research shows ratios don’t significantly affect quality but dramatically affect cost. British childminder numbers fell 50% between 2013 and 2023 from regulatory burden alone. Relaxing ratios to European norms would expand supply immediately. Cost: zero.

OFSTED registration. Requiring childminders to document curriculum progress for infants creates compliance burden without improving care. Replace it with basic safeguarding checks. Cost: negative.

Planning reform. Liberalize permission for family-friendly housing (extensions, granny annexes, standardized designs). The constraint is political will, not money.

This doesn’t mean spending never helps. Stone’s meta-analysis shows cash transfers have consistent effects (and yes I would spend 10% of GDP on family policy if given the chance). But “we can’t afford pronatalism” is a really bad way of thinking about things, and often cause people to miss low hanging fruit.

Q12: Conservatives have more children than liberals. Doesn’t that mean conservative values produce higher fertility?

At the individual level, yes. At the system level, the opposite is true.

Individual conservatives have more children than individual liberals. But countries with conservative policy regimes have lower fertility than liberal ones. The Nordics and France outperform Southern Europe. Catholic Italy and Spain have Europe’s lowest fertility despite cultural emphasis on family. So we have a situation where social conservatives thrive and live their best lives under generous welfare states.

POSIWID resolves the paradox. What matters isn’t what a system values. It’s what it produces.

Conservative values say family is important. Liberal systems remove barriers to family formation. Traditional societies say “have children” while their systems say “good luck.” People respond to the system.

France and northern Western European countries have high fertility because their systems.

That said, Western European governments are now dismantling these decades-old systems since the Great Recession, with lots of academic research confirming the results. Meanwhile in Eastern Europe, right-wing parties sometimes advocate for family spending, as Stone would gladly attest. In Poland, Slavoj Žižek notes it was the right-wing PiS who implemented universal healthcare, not the left.

The question isn’t whether you value family. It’s whether your system removes barriers and risk that prevents family formation.

Q13: Does keeping women out of the workplace increase birth rates?

No. The evidence points in the opposite direction.

International data shows higher-earning women have more children:

Netherlands: Administrative records found men and women with higher personal incomes had higher birth rates, with the highest-earning women having 60% higher birth rates than the poorest.

Japan: Working women with career ambitions show higher fertility intentions. Women planning for children were nearly twice as likely to hold stable, regular employment. Career advancement motivation scored significantly higher among women with fertility intentions.

Germany: Job creation in female-dominated industries (healthcare, education) boosts birth rates. A 1% increase in female-dominated jobs correlates with a 0.01 increase in fertility rates. Women in non-regular employment express half the fertility intentions of regular employees.

Sweden: Women’s income association with birth rates shifted from slightly negative to positive over time. In recent cohorts, earnings of mothers with 1-3 children exceed those of childless women.

It’s not employment that suppresses fertility. It’s economic precarity and it reinforces the fall in maternity rates that Shaw demonstrates. Stable employment in family-friendly industries with higher incomes enables both career and family formation. Women in irregular, low-paying jobs have lower fertility intentions and outcomes.

The brief historical period when richer people had fewer children is ending. We’re returning to the ancient norm: higher-status people having more babies.

Part V: The Coalition Problem

Q14: Who’s giving pronatalism a bad name?

The evidence base for barrier-removal pronatalism existed decades before Elon Musk discovered that tweeting about population collapse generates engagement.

South Tyrol started in the 1980s. Akashi began in 2011. Minamiminowa’s transformation started in 2005. Yeonggwang has led Korea for six consecutive years. None of it required the likes Musk or Hanania.

Musk is a late arrival polluting a conversation that should be about implementation.

He warns about civilizational collapse while implementing RTO mandates as an explicit “attrition tool” (his word with Vivek Ramaswamy: forced office return “would result in a wave of voluntary terminations that we welcome”). Research by Nicholas Bloom estimates this costs roughly 100,000 births annually compared to hybrid work.

Apply POSIWID: What does Musk’s system produce? Brand value about demographic concerns, plus labor cost savings through attrition. What doesn’t it produce? Babies.

Hanania calculates “ideal fertility rates” of 4-8 per woman while dismissing the framing that people want more children than they have. He says he “thinks less of” childless people and wants childlessness “negatively marked in the broader culture.” That’s not barrier removal. It’s demographic engineering through social coercion.

Deming had a word for reacting to every fluctuation as if it were a special event: tampering. The online discourse is chronic tampering. Every Musk tweet becomes representative of “pronatalism.” Every quarterly fertility number triggers hot takes. Tampering makes systems worse, not better.

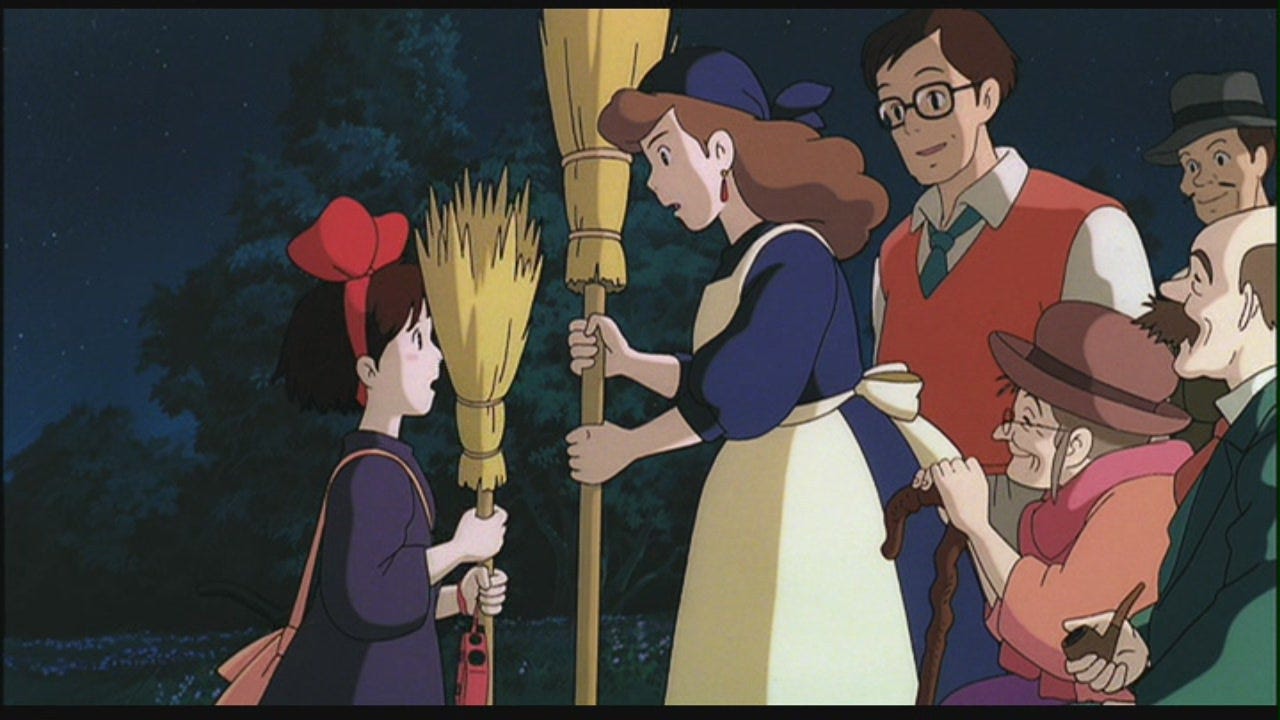

Here’s what baffles me: we have Hayao Miyazaki.

Miyazaki is a known pronatalist who advocates supporting young families. His films celebrate childhood, family bonds, intergenerational care, rural community, the natural world children should inherit. He’s as famous as Musk globally, more beloved, less controversial. His entire body of work is an argument for why children matter and what kind of world we should build for them.

And yet the discourse is hellbent on making Musk and his hangers-on like the Collins couple the face of pronatalism.

Q15: Why does the discourse seem disconnected from what works?

Because online incentives produce engagement, not outcomes, and you can’t avoid that with a name change. If there’s any hope of changing the tide, it requires better organization and coordination from the less deranged parts of the discourse, regardless of whether they’re progressive, conservative, or eccentrics like myself.

Effective systems require feedback from outputs to decision-makers. Online advocacy gets instant engagement metrics but zero feedback about policy outcomes unfolding over years.

The always-online pronatalist discourse systematically focuses on worthless grandstanding: terminology fights, coalition policing, responding to provocateurs, symbolic positioning. The vital few (cesarean rates, VBAC access, housing costs, employment stability, childcare logistics) get ignored because they’re boring, technical, and don’t generate engagement.

The real-world interventions most likely to succeed are precisely those least likely to go viral: remote work policies , budget reallocations are unglamorous municipal finance, forty years of sustained payments is the opposite of viral, Yeonggwang’s 80+ lifecycle-connected support policies require reading Korean local government documents.

What generates engagement? Calculating “ideal fertility rates.” Tweeting about civilizational collapse. Fighting about terminology.

Ledbetter writes that pronatalist “advocacy for mothers seems quiet to nonexistent.” Quiet, yes. Because the boring operational work that takes decades happens where engagement metrics don’t reach.

Q16: There’s a genre arguing “nothing works.” Is that sophisticated or defeatist?

Defeatist, and wrong.

If nothing works, explain the variation from local governments and national benefits. Why is Japan have higher fertility rates than poorer countries in East Asia? Why does France have higher rates in America? Why does this city that “does something” have higher rates than the city that does “nothing”.

“Nothing works” requires treating national averages as the only data and dismissing subnational variation as noise. But the variation is the evidence.

The tell is when critics invoke Romania’s Decree 770 as if that’s what most pronatalists propose, despite decades of counterevidence. Forced gynecological monitoring isn’t barrier removal. Conflating the two lets critics attack a strawman while ignoring actual proposals.

Juran taught that poor quality isn’t free. It costs more through rework, waste, inspection, and failure. The “nothing works” crowd treats the “poor quality” status quo as costless default. It isn’t.

Every traumatic birth that deters subsequent pregnancy is a cost. Every young man whose employment instability prevents family formation is a cost. Every woman who wanted children but couldn’t because of macro factors is a cost.

The question isn’t whether intervention is expensive. The question is whether the cost of intervention exceeds the cost of continued system failure. “Nothing works” is an accounting error that ignores the losses already accumulating.

Back To My Point (and the Regular Scheduled Programing)

Edward Deming’s most humane principle: drive out fear. When women fear traumatic births, they don’t have more children. When young men fear economic instability, they don’t form families.

But here’s what I’ve avoided: what “building” actually requires.

I’ve spent 4,000ish words criticizing discourse while participating in it. What have I produced? Another Substack essay. Not changed hospital policies, passed legislation, or supported mothers.

We just really don’t need more terminology debates.

Even in the pronatalist online sphere, people still haven’t never heard of Akashi, South Tyrol, or Yeonggwang. They only hear false cliches about how xyz policy failed, when it didn’t. They’ve only heard Musk tweeting about collapse. When someone says “pronatalist,” they picture Hanania calculating fertility rates, not free diapers delivered by healthcare workers.

That’s the problem. We need to make the boring work less boring. How do we show more people what forty years of commitment looks like.

This is really comprehensive and useful - thanks for writing it!

I sign off on 90+% of this view of what the pro-natalism movement should be about, but insisting on sticking behind the widely unpopular banner of "pro-natalism" is still such a misstep. A name like “pro-child” is much harder to co-opt because the name carries intrinsic meaning and emotional resonance. Plus, the name pro-natal has already been co-opted.

It would take a tremendous effort to get the name "pro-natal" to have broad public appeal, and the effort could easily be undone by the people who have already co-opted the name. You also go into great detail about the importance of systems, but if you think about the role of the word “pro-natal” in the system, it is alienating potential allies, dampening public support, and making the pro-natalist movement much easier to ignore.

The pro-natal movement is good, but it can be much stronger and much more likely to succeed if it changes the name and more directly acknowledges the concerns of the women who ultimately have to decide to have kids. I wrote more about why the name is so counterproductive here, if you're curious: https://modernshakers.substack.com/p/ill-never-call-myself-a-pro-natalist