Why Does Raising the Retirement Age Hurt Young People? What Would It Take to Start/Restart Their Careers?

Governments worldwide are trying to shore up pension systems by pushing back retirement ages. But cost-saving measures has a lot to do with gutting the future tax base, as well

A friend forwarded me a Twitter conversation he thought I would find interesting. The thread started innocuously enough. Lyman Stone was responding to Moses Sternstein analysis about the COVID "pull-forward" retirement wave: millions of people who retired earlier than planned during the pandemic, creating the "labor shortage" that drove wages and inflation up.

He made an interesting claim: "In fact, virtually all cuts to Social Security work this way: if you reduce Social Security, retirees keep working longer, employers are hesitant to fire senior workers, etc. One of many interactions OASDI does not actually entertain!"

Stone had articulated something I'd been sensing but couldn't quite name. The standard rhetoric used to justify Social Security cuts and increase retirement ages completely ignores how those cuts destroy younger workers' careers. When someone asked him for solutions, his answer was blunt: "There's no solution except higher birth rates or rapid productivity growth."

The idea of delayed retirement crushes young workers' advancement prospects seems like a no brainer (that somehow never brought up in debates on raising the retirement age of Social Security), but something else is still missing.

The Labor Market Paradox

The Narrative: By every traditional measure, this should be a golden age for young workers. Unemployment (U3) sits at 4.1%. Business formation hit records with over 5.5 million new companies registered in 2023 alone. GDP growth remains robust. Young people are told they have options: get a college degree for white-collar work, or skip the debt and go into trades for "more secure" jobs with six-figure salaries, freedom to work for yourself, and hands-on skills that can't be outsourced to AI.

The Reality: Workers under 40 report feeling trapped in "career purgatory." We are seeing a rise of long-term unemployment, declining hiring rates, and college graduates struggling to find work even in jobs that don't require degrees. Career advancement feels nearly impossible. Home ownership and family formation rates continue declining among young adults. If you are unemployed, you face Great Recession-level risks of long-term unemployment, and if you become long-term unemployed, the prospects for recovery are dire with a good chance it's just game over.

The crisis now affects both paths young people were told to follow. Graduate unemployment has climbed above the overall unemployment rate for the first time on record. Male graduate unemployment rose from less than 5% to 7% over the past 12 months, completely erasing the college employability premium. Recently graduated young men are now unemployed at the same rate as their non-graduate counterparts.

But the trades aren't offering refuge either. Despite the narrative about trade jobs being safer, building inspectors, electricians, and plumbers face unemployment rates of 7.2%, more than three times that of (formerly) entry-level office jobs like budget analysts. Trade roles dominate the bottom of rankings for best entry-level jobs, with welders, automotive mechanics, and boilermakers among the least promising career starters.

After years of analysis blaming millennials' economic struggles on smartphone addiction and delayed maturity, observers like Jean Twenge now wonder why young people still aren't having families despite 'good' economic indicators, besides blaming it on the phones or whatever excuse to blame someone for not having economic stability. The disconnect suggests these commentators were looking in the wrong place all along.

The disconnect suggests we're overlooking a crucial mechanism in how the modern economy actually works. Stone's insight provided the first clue.

The First Clue: COVID Retirement Experiment

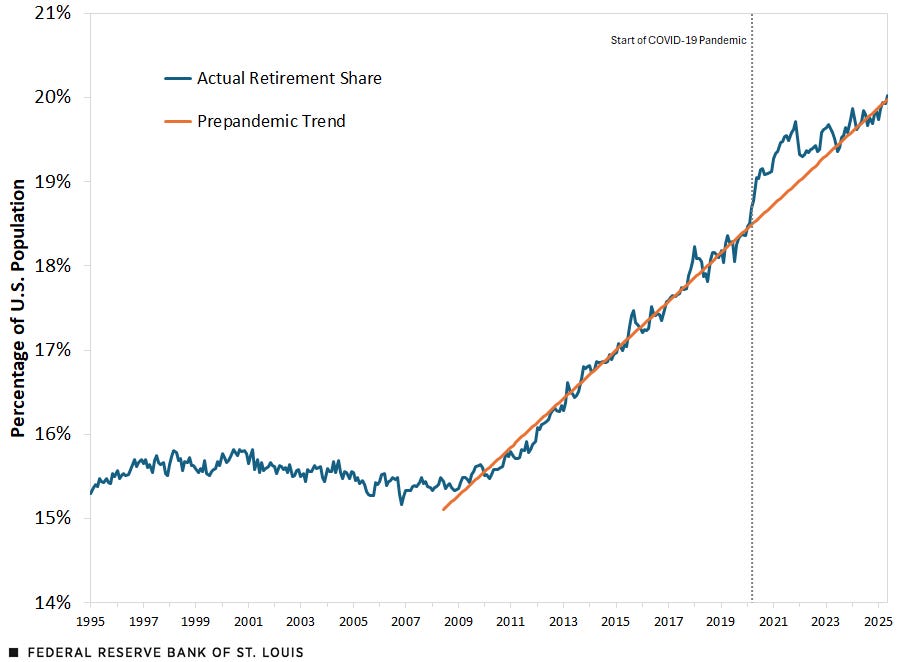

The COVID-19 pandemic accidentally created the largest unplanned retirement experiment in modern American history, providing crucial evidence for solving our mystery.

During the COVID crisis, the Federal Reserve documented over 2.4 million "excess retirees": people who left the labor force above what pre-pandemic trends would have predicted. This wasn't simply early retirement by choice. The pull-forward was heavily concentrated among workers aged 55 and older without college degrees, particularly those in jobs that couldn't be performed remotely. These weren't the highly compensated professionals who could afford early retirement; they were often the most economically vulnerable workers, caught between virus exposure and business shutdowns.

The sudden exodus created an immediate labor shortage that drove unprecedented wage growth, especially for the youngest workers. From the fourth quarter of 2019 to the first quarter of 2023, nominal wages grew by an extraordinary 25% for workers aged 16-19 and 28% for those aged 20-24. This far outpaced the 18% growth for prime-age workers and the mere 13% for workers aged 55 and older.

Young workers suddenly had bargaining power they hadn't experienced in decades. The "Great Resignation" saw millions of low-wage workers quit for better pay and conditions. Entry-level positions that had been scarce suddenly offered signing bonuses.

But by 2023, the excess retirements had been absorbed back into expected demographic patterns. The dramatic wage growth slowed. The labor market "normalized" except for one puzzling feature: simultaneous low unemployment and low job growth. Who doesn’t get hired if there are no jobs? People currently unemployed, who are disproportionately under the age of 35.

The youth labor market reveals the deeper structural problems. While overall unemployment appears benign, the youth unemployment rate in OECD member countries stood at 11.49% in 2024, consistently and significantly higher than that for the adult population, with December 2024, the OECD youth unemployment rate was 7.0 percentage points higher than the rate for workers aged 25 and over. Nine OECD countries reported youth unemployment rates above 20% as recently as April 2024.

More troubling is the quality of available jobs. In the European Union, an analysis covering the period from 1985 to 2019 found that the wages of workers over the age of 55 grew nearly twice as fast as those of workers under 35, an increase in the age wage gap of 96%. A 2020 Brookings Institution analysis found that "44% of all U.S. workers (53 million people) earn low wages, with a median hourly pay of just $10.22." Critically, two-thirds of these low-wage workers are in their prime working years (25-54), and over half work full-time, year-round.

Young people are disproportionately funneled into precarious employment. Across the EU, a staggering 43.3% of employed 15- to 24-year-olds were on fixed-term contracts in 2015, a figure more than three times higher than the 14.1% rate for the overall workforce. In countries like Slovenia, Poland, and Spain, the share of young workers on temporary contracts exceeded 70%.

The COVID experiment revealed how retirement timing affects youth opportunities, but it was temporary. Stone's insight points to a more persistent problem: what happens when retirement is systematically delayed rather than accelerated, especially as countries are pushing for later and later retirements. To understand the full impact, we need to look inside individual companies. Fortunately, detailed firm-level studies provide concrete evidence of exactly how this mechanism works.

Inside the Promotion Bottleneck

Firm-level studies from Europe provide concrete evidence for Stone's thesis. When older workers delay retirement by just one year, the effects on their younger colleagues are immediate and severe: annual wage growth drops by 2.3% to 2.5%. More dramatically, the number of younger workers promoted into managerial roles falls by nearly 50%. For white-collar positions, promotions drop by about 21%.

This isn't about overall employment levels. This is about the internal architecture of firms. When the person above you doesn't retire, your promotion doesn't happen. When promotions don't happen, wage growth stagnates. When wage growth stagnates across an economy, you get exactly what we're seeing: low unemployment that somehow doesn't feel like a tight labor market.

The phenomenon even has a name: "occupational downgrading." Skilled young workers, unable to advance in their chosen fields, take lower-skill positions just to maintain employment. An engineering graduate becomes a technician. A business school graduate takes an administrative role. The human capital that should be driving productivity growth gets systematically underutilized.

It accounts for why there are fewer management positions available and why career advancement has become so difficult, why wage growth has been disappointing despite low unemployment, and showcases a significant blind spot in Social Security policy modeling.

This explains why young people struggle to advance in their careers, but it doesn't explain why they're also struggling to start careers. Something else is affecting career entry. Promotion bottlenecks shouldn't prevent companies, especially newer companies, from hiring new graduates for entry-level positions. Young workers should still be able to start their careers, even if advancement is slow (or lets be honest here, it’s non existent), because if an economy grows there should be demand for highly educated (cheaper and more disposable, increasingly on contract) workers and technicians.

Instead, we are seeing the opposite trend

The Second Clue: The Missing Companies

If the problem were purely demographic, we should see strong job creation at entry-level positions as businesses expand to meet demand with available younger workers. We should see new businesses forming to take advantage of all that skilled young talent being held back by promotion bottlenecks, especially at cheaper prices and destroyed expectations.

The only ones hiring young workers right now are gig apps like DoorDash, Uber, and OnlyFans. These platforms were designed for extra cash, not full-time jobs. When college graduates are driving for Uber or delivering food as their main source of income, that shows how completely the traditional job market has broken down.

Instead, we see the opposite. Between 2020 and 2023, new software company formation fell by 86% in the US, 89% in Israel, and 87% in the EU. Something is systematically choking off the creation of new companies, in addition to the current Fed Rates, that would typically absorb young workers eager to start their careers.

As former investment banker Darin Soat of How Money Works has documented, this problem becomes clear when examining broader American market data. Despite record business formation in recent years, the number of publicly traded companies has collapsed. In 1996, 8,090 companies were publicly listed on American stock markets. Today, despite the economy being three times larger and markets handling seven times more capital, fewer than 4,000 companies trade publicly.

This decline matters because new businesses are the primary engine of net job creation in developed economies. The Census Bureau shows a decades-long downward trend in the establishment entry rate, from around 14% in the early 1980s to about 10% in recent years. This decline in business dynamism directly translates into fewer new jobs per business, slower aggregate wage growth, and a less competitive marketplace.

Startups/Scaleups/SMEs don't just create jobs. They create the right kinds of jobs for young workers at all levels of education, from accountants, marketers, customer service, etc etc . New companies typically hire younger workers who are willing to accept lower initial wages in exchange for rapid skill development, promotion opportunities, and equity stakes. Established companies prefer experienced workers for most positions and use their established hierarchies for advancement.

When new business formation (besides sole props and gig contractors) collapses, it eliminates the primary mechanism by which young workers enter the professional workforce outside of service industries. Young workers face constraints from two directions: fewer promotion opportunities within existing firms (due to delayed retirement) and fewer alternative career paths at new firms (due to declining business formation).

Consolidation Engine

What's happening to all these businesses? They're getting bought before they can grow. The venture capital industry figured out it's more profitable to build companies specifically to sell them than to actually compete.

The M&A Employment Impact

M&A activity fundamentally disrupts workforces. When companies combine, "overlapping functions in areas like human resources, marketing, finance, and administration are deemed redundant," leading to job cuts that "disproportionately affect the employees of the acquired company."¹

More systemically, M&A increases employer market power. A detailed study of takeovers in the Netherlands found that even four years after an acquisition, workers from the target firm earned, on average, 2.8% less in labor market income and worked 7.3% fewer hours. Research on hospital mergers found that in deals that significantly increased market concentration, annual wage growth for skilled workers was suppressed by as much as 1.7 percentage points, i.e. eroding nearly a third of typical yearly wage growth.

Killer Acquisitions

Just to show why companies acquire smaller companies, a study tracking over 35,000 drug development projects found that "about 6.4% of all acquisitions were killer acquisitions" (deals where incumbents buy competitors specifically to shut them down.) In the technology sector, the five largest tech firms made 175 acquisitions between 2015 and 2017 alone, and subsequently discontinued more than 60% of the acquired products or services.

The Kill Zone Effect

This creates what has been termed "kill zones" around dominant platforms. Potential entrepreneurs and their investors see little point in developing competing products, knowing they will likely be either copied or acquired and buried by the incumbent. The net result is an economy with fewer large employers, a dearth of new employers, and a suppressed rate of innovation.

Private equity firms now control vastly more capital than in 2000, keeping promising companies private rather than letting them go public. Seven companies now control 34.1% of the entire S&P 500, up from just 16.2% for the top ten companies in 2015. The same three asset management firms (BlackRock, Vanguard, State Street) hold major stakes in competing companies across entire industries, using funds from pensions, both public and private, to consolidate control.

When your biggest shareholders own all your competitors, competition becomes coordination. The traditional escape route for young workers (jumping to a growing startup) gets systematically eliminated through acquisition before those companies can scale and offer genuine career opportunities.

Israel's Experiment: How to Kill Your Own Industry

A case study from American Affairs Magazine (Scale-Up Nation: The Role of IP-Transfer Restrictions in Israel’s Industrial Policy by Erez Maggor) provides evidence of this dynamic. Erez Maggor's analysis of Israel's industrial policy shows how the conflict between building domestic champions and optimizing for M&A exits affect young workers.

Phase One: Building Industrial Capacity (1970s-1990s)

From the 1970s to 1990s, Israel had a simple rule: if you take government money for research, you have to build your factories in Israel and keep your intellectual property here. The Office of the Chief Scientist (OCS) administered this system with strict conditions: "all products emerging out of OCS-funded projects must be manufactured exclusively in Israel, and the IP created during the R&D stage must not be transferred beyond the state's borders."

As former chief scientist Dr. Yehoshua Gleitman explained: "We want to help nurture an industry that will employ workers." The system worked. Given Imaging, which pioneered endoscopy capsule technology, was required to establish manufacturing in Israel and eventually employed close to a thousand workers.⁵

Phase Two: The "Start-up Nation" Model (1990s-Present)

Then in 1993, Israel launched Yozma, spending $100 million to create venture capital funds. The new rule was simple: build startups fast and sell them for maximum profit. In 2005, the R&D Law was reformed, lifting "the outright ban on the transfer of IP and replacing it with a fee."

The results looked impressive. Israel became the "Start-up Nation" with record $15.8 billion in acquisition deals in 2024. But instead of building the next Intel in Israel, entrepreneurs built companies specifically to be bought by Intel. When Intel bought Mobileye for $15.3 billion in 2017, Israel lost what could have been their first major car technology company.

The Employment Impact

The employment effects were dramatic. "For each employee of an Israeli high-tech manufacturer, two additional local jobs in nonmanufacturing industries are created. Each R&D center employee, on the other hand, creates only one-third of an additional job." Despite billions in exits, most Israelis didn't benefit from the tech boom. As Dan Breznitz observed: "During the years of extreme high-tech growth, the rest of the economy enjoyed no positive spillovers."

Policy Choice, Not Market Forces

Israel's experience proves these outcomes are policy choices, not natural market forces. The original OCS model successfully built industrial capacity through government intervention. The Yozma model destroyed it through different government intervention. Both were deliberate policy designs with completely different incentive structures.

The same pattern emerges in American data. The collapse in publicly traded companies didn't happen because markets naturally consolidate. It happened because policy changes made private equity more attractive, merger review standards weakened, and tax policies favor quick exits over long-term building.

When the same asset managers own competing firms across entire industries, it's the breakdown of competition rather than some market efficiency. The Israeli case study proves that what we call "market outcomes" are actually the result of specific government policy choices about how to structure incentives.

Solving the Mystery: Two-Directional Career Destruction

Stone's retirement insight and the business formation collapse work together to create a perfect trap for young workers.

The Pincer Movement

Traditionally, workers blocked from promotion had an escape route: jump to a growing company with rapid advancement opportunities. But that safety valve no longer exists. The same forces that make advancement impossible within firms should create demand for ambitious young talent at new companies. Instead, new companies are systematically eliminated through acquisition before they can scale.

The Result

You can't advance at your current job because delayed retirement blocks promotions. You can't jump to a growing startup because they're designed for quick acquisition, not independent growth. You can't realistically start your own company because you lack the capital, connections, and safety net required, and even if you could, the venture capital system optimizes for exits, not competition.

This explains the central paradox: how an economy can simultaneously produce impressive headline statistics (low unemployment, record business formation) while systematically destroying career pathways for an entire generation. We're measuring business creation while ignoring business elimination. We're tracking job numbers while missing job quality.

The economy has been optimized for metrics that look good in policy reports while undermining the mechanisms young workers need to build successful careers.

The Path Forward

The solution requires practical action, not more measurement. There is a lot to discuss on things, both big and small, which is out of scope for this article.

We do need to abandon failed approaches. We can't cut Social Security/public pensions, impose means testing, or raise retirement ages. These worsen promotion bottlenecks. We can't pretend what's happened to young people since 2008 is acceptable. On that note, Blanket forced retirement would be destructive, especially for founder-led companies, which could nasty long term side effects.

There is no way getting out of this except by boosting birth rates and achieve rapid economic growth. Not the failed post-2008 methods of financial engineering or wishcasting, but genuine good governance especially in industrial, youth, and familu policies.

If I am forced to give you a starting point, it would be with energy. As mattparlmer documents in "America Can Beat China on Energy," Chinese manufacturers pay $0.09/kWh while California companies pay $0.24/kWh. When electrons cost three times more on one side of an ocean, industrial capacity goes to the other side. A massive American energy buildout targeting $0.01/kWh electricity would create millions of jobs across skill levels: electricians, engineers, technicians, project managers. Real careers with advancement potential, not gig work. It requires a lot of political will, YIMBY reforms, the willingness to tax the upper crust until the Fed and bond markets are forced to be reasonable about cost of capital without giving them a tribute of unemployment, and stepping on a lot of other people’s toes.

Erez Maggor's Israeli case study shows how government investment can build domestic industrial capacity instead of feeding acquisition targets. When Israel switched from building domestic companies to optimizing for startup exits, each high-tech manufacturer job was replaced by R&D jobs that created one-third as many supporting positions. The country got impressive acquisition headlines but lost the broad-based employment that builds middle-class prosperity.

Palmer shows how energy infrastructure creates the fundamental input advantage needed for competitive manufacturing. We need antitrust enforcement to break up consolidated industries (read Matt Stoller and Basel Musharbash for more). We need industrial policy that creates genuine companies with career ladders, not startups designed for quick exits.

For workers (white and blue collar) under 40, this helps determines whether you'll afford a house, start a family, or retire with dignity.

I agree with the ultimate point that it’s all about finding a way to raise birth rates, and investing in clearly useful industries like energy buildout (and on-/friend-shoring those supply chains) makes a lot of sense. (Now if we can just convince the US government to not keep their heads in the sand…)

Though on some specifics, RE why startups went off a cliff from 2020-2023, you mention the Fed rates as one factor but not fully explanatory of the decline - doesn’t that explain most of it? As an entrepreneur myself I hear from other founders that it’s hard to raise money these days, along with general worry about not being able to bounce back if they don’t make it - a riskier environment to make a startup.

(I’m insulated from this since my company is bootstrapped, outside of the SV tech bubble, and taking a small business early profitability approach, but maybe that’s just another reflection of a more risk-averse approach to business creation 🤷)

And I haven’t really heard of people seeing a lucrative acquisition as being a bad outcome for a startup that would drive them to not want to build one altogether (though I agree that it’s not great for the ecosystem of jobs and competition). After all if a company felt that they could get a better outcome by not taking an acquisition, they could just not take it, but they are (especially in this market).

RE hiring young people for cheaper with the expectation of growth in the world of software, it seems like the age of LLMs isn’t helping, where an LLM can take a newbie to being a more productive but still junior engineer, whereas it takes a knowledgeable and motivated senior to being a 10x developer—which in my case means getting away with a much smaller and manageable team. Seems nobody wants to hire junior developers anymore, to the industry’s long-term detriment, though I think this has little to do with retirement ages or social security spending, at least in software.

Anyway thanks for the post!

I think you're missing a lot of nuance in this story, and the focus on antitrust is a hammer in search of a nail.

--during the labor shortage, two things happening at-once: (1) massive boon to lower-wage service workers, as non-college unexpectedly retired. These aren't "entry level" jobs in the sense of 'climbing the corporate ladder' so much as waiters, drivers, home healthcare aids, retail clerks, etc.--largely filled by "foreign born" workers; and (2) massive influx of cheap capital that super-charged company formation, and 'white collar' hiring in tech, finance, etc.

The latter ended when cheap capital ended. All companies, but especially tech companies, started to cut burn, headcount, etc. Companies got lean.

The former hasn't fully 'ended' because as we age, the share of non-workers will grow, putting pressure on the bodies that we have...but it's still not going to benefit 'entry level' college grads, unless they decide to enter the skilled trades (which perhaps they should).

Importantly, the gap is worse for men than it is for women. Why? Because healthcare (again, aging) is an increasingly large share of the economy, and healthcare skews female.

All of which is to say that the reason hiring has slowed is because *growth* has slowed. Data Centers are basically the only pro-cyclical sector that's in expansion right now. Healthcare is acyclical, it's growing, and its hiring.

Antitrust have very little to do with any of this, other than likely hurting more than it helps.

--re. antitrust, a big part of why companies stay private longer is because the regulatory burden of going public is too costly, relative to privates. Enough capital has been raised on the private side that the best companies no longer need to go private. If you want more public cos, you need less regulation, not more

--pe is extremely competitive, so the idea that pe ownership somehow creates a cartel on company formation is just wrong. if anything, it's the opposite, where pe capital is perhaps more money than good risks to chase. if certain wages fall post PE acquisitions it's mostly likely because *all costs fall* because that's part of what PE does--they find operational efficiency, which yes, includes trimming the fat. And achieving economies of scale through consolidation isn't anti-competitive, and is extremely pro-consumer.

--in fact, the antitrust crackdown on ad tech acquisitions, for example, crushed the ad tech startup landscape, bc building and exiting to Meta, Google, etc. was a path to monetization. Instead of having to look over their shoulders at upstarts, Meta etc. breath easy bc antitrust regulators killed the competition, they didn't help it.

At the end of the day, there is no bigger cartel (literally) than the US government. The notion that a singular body with nationwide jurisdiction and no competition can and should by horizontal integration determine the business outcomes for every business, shareholder, worker, and consumer in the country in *furtherance of competition* is a contradiction in terms. If you see cartelized activity as bad because without competition, firms are less responsive to consumers and lack the incentives to deliver optimal goods and services, then consider how that logic applies to the FTC and its provision of goods and services.