Recycling Is (Not) a Scam: Captain Planet’s “The Power Is Yours” vs State Capacity

How "The Power Is Yours" Became the Greatest Environmental Misdirection of a Generation

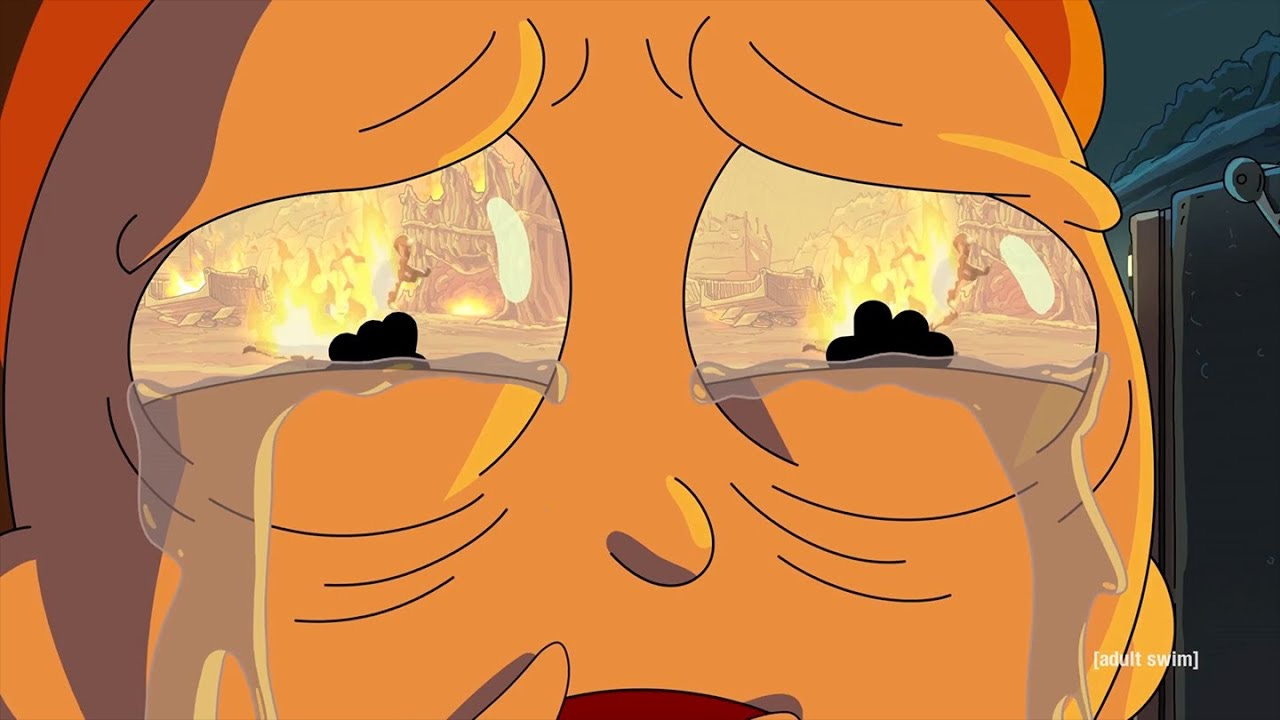

If you grew up in the 1990s, you know where that faith in sorting came from. You probably remember Captain Planet: five teenagers from around the globe, each bearing a magic ring representing an element, summoning a blue-skinned superhero to battle eco-villains with names like Hoggish Greedly and Looten Plunder. The show’s message was unmistakable. Environmental salvation lay in individual action. “The power is yours,” Captain Planet reminded viewers at the end of every episode.

We absorbed that lesson. We learned to sort our recyclables, turn off lights, take shorter showers. Reduce, reuse, recycle. An entire generation internalized the idea that if we just made the right choices, we could save the planet one aluminum can at a time.

In 2018, the recycling system broke.

China’s National Sword policy banned imports of most recyclable waste, imposing contamination thresholds so strict that American sorting facilities couldn’t meet them. 111 million metric tons of plastic waste were displaced with nowhere to go. Communities across America halted or curtailed recycling programs. England burned half a million more tonnes of plastic in the first year alone. Prices for recovered paper collapsed by more than 300%, leaving Europe with a structural surplus of 7-10 million tonnes.

It turned out we weren’t recycling. We were exporting the problem. When China said no more, we discovered that the system, one that we thought we were slowly but surely bringing forth, was mostly a con job.

Laura Leebrick, a manager at Rogue Disposal & Recycling in Oregon, watched an avalanche of plastic pour into her landfill after China closed its doors. Containers, bags, packaging, strawberry containers, yogurt cups. None of it would become new plastic. “To me that felt like it was a betrayal of the public trust,” she told NPR. “I had been lying to people... unwittingly.”

This wasn’t a singular shock. Two years later, COVID-19 revealed that American medical supply chains depended on Chinese manufacturing. Hospitals ran out of masks and ventilators. We discovered we couldn’t make the things we needed to survive a pandemic. In 2022, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine exposed European energy dependence on Russian gas. Germany scrambled to find alternatives while prices spiked globally. Now, tariff wars are exposing dependencies across sectors: rare earth minerals, semiconductors, basic industrial inputs. We keep discovering fragility where we assumed resilience.

The pattern is consistent. Systems that looked functional were actually dependent on international arrangements we didn’t control. When those arrangements broke, we discovered we had no domestic capacity. We had outsourced not just production but the capability to produce. And in each case, a comforting story had masked the underlying vulnerability. For energy, it was the assumption that markets would always provide. For manufacturing, it was the promise of globalization’s efficiency gains. For recycling, it was Captain Planet.

That message was something you could say is “technically correct.” While children learned that they had the power (just not the kind they think), corporations continued using cheap, non-recyclable materials and externalizing disposal costs onto municipalities and taxpayers. The framing shifted blame from producers to consumers. It made environmental degradation a problem of individual virtue rather than institutional design. Which in turn led a lot of people (in good faith, mind you) eager to save the environment to waste their time and energy going after the wrong things.

The framing created the illusion of action without teaching how things work. Sorting your bottles feels like doing something. It satisfies the psychological need to respond to environmental anxiety. But that feeling of agency can substitute for, rather than complement, political engagement. Why demand Extended Producer Responsibility legislation when you’re already “doing your part”?

And it provided cover for corporations to continue externalizing costs. Less than 9% of all plastic ever produced has been recycled. But the recycling symbol is there on the package, so consumers feel absolved, and manufacturers face no pressure to change.

Here’s what makes this worse than mere negligence: the industry knew. A joint investigation by NPR and PBS Frontline uncovered industry documents from as early as 1973 calling plastic recycling “costly,” sorting it “infeasible,” and concluding there was “serious doubt that it can ever be made viable on an economic basis.” They knew for two decades before Captain Planet aired.

Yet in 1989, as public anger about plastic waste mounted, Larry Thomas, president of the Society of the Plastics Industry, called executives from Exxon, Chevron, Amoco, Dow, DuPont, and Procter & Gamble to a private meeting at the Ritz-Carlton in Washington. “The image of plastics is deteriorating at an alarming rate,” he wrote. “We are approaching a point of no return.” The solution? A $50 million annual advertising campaign promoting recycling they knew wouldn’t work at scale.

“If the public thinks that recycling is working, then they are not going to be as concerned about the environment,” Thomas later told NPR.

Captain Planet premiered in 1990. The industry’s heaviest advertising push launched the same year. “The bottle may look empty, yet it’s anything but trash,” said one industry ad. “It’s full of potential.” The show and the ad campaign delivered the same message. Whether Turner coordinated with the industry or simply absorbed the cultural air they were pumping, the effect was identical. Captain Planet wasn’t created by the plastics industry. But it couldn’t have served their interests better if it had been.

The Bad Guys

Captain Planet’s critics (and there are many in environmental studies programs, which may surprise people who assume environmentalists embrace any pro-environment media) point to something revealing about the show’s villains. Hoggish Greedly, Looten Plunder, Verminous Skumm, Sly Sludge. They’re caricatures: physically deformed, often coded as lower-class, cartoonishly evil figures.

The villains work almost exclusively in extractive industries (timber, mining, oil, energy) and we never see examples of this work being done responsibly. One villain is literally a garbage collector. The lesson, intended or not, is that environmental harm comes from bad people doing bad things. Mustache-twirling evildoers.

Most environmental damage is a byproduct of essential services we all use. We don’t rip trees out of the ground for fun; we do it to build homes and make paper. We don’t drill for oil to dump it on the ground; we drill because people buy gasoline to get to work. Most of the infrastructure and production is designed around large batches, meaning it’s all fixed and semi-fixed costs and reducing consumption just might mean more waste and poverty. We only lower environmental impacts by better processes, technology, and regulation! Not by blocking housing, clean energy, transit or whatever. The show was conceived and funded by Ted Turner (who, last we checked, can’t twirl his mustache), who owned the TV stations that broadcast it, and who has a non-zero number of private jets.

Captain Planet taught children that the problem is bad folks, not hard problems (+ bad folk in suits as we see with Larry), and that when people disagree it’s because they are monsters who love to destroy beauty. That people, by showing not by telling, are pollution. This helped poisoned the political well for a generation, and distracted people from the real threats.

Environmentalists learned to see workers in extractive industries as obstacles and afterthoughts rather than allies whose livelihoods depended on the industries needing transformation. Workers needed credible alternatives. What they got: retraining programs disconnected from labor markets, “just transition” funding that never materialized, communities abandoned with nothing substantive. Politicians made promises without follow-through. In short, they got downward mobility at best.

Captain Planet wasn’t alone in this. The Simpsons, which premiered a year earlier, gave us Homer Simpson: the incompetent, safety-indifferent nuclear plant worker whose bumbling threatens meltdowns, employed by the villainous Mr. Burns. Across 1990s television, extractive industries were staffed by monsters and nuclear power was overseen by buffoons. France, which built its nuclear fleet during these same decades, offers the natural comparison. We might ask whether that cultural priming contributed to America and Western Europe’s failure to build nuclear capacity during precisely the decades when climate change demanded it.

Who Are The Real Antagonists (Who Target Systems, Not Just Rivers)

The critique of Captain Planet’s villains can be taken too far. It would be easy to conclude that there are no bad actors, just hard problems and misunderstandings. That’s not our view.

There are antagonists. But they don’t look like Hoggish Greedly dumping toxic waste while cackling. Real villainy targets systems, not rivers. The actual bad actors operate through lobbying, regulatory capture, and strategic information control. The battlefield isn’t the forest; it’s the statehouse.

Consider the plastics industry’s promotion of “chemical recycling” (also called “advanced recycling” or “molecular recycling”) as a technological solution to plastic waste. Investigations by NRDC and Beyond Plastics reveal that these technologies are largely plastic incineration by another name. Pyrolysis accounts for 80% of U.S. “chemical recycling” facilities. Most produce dirty fuels rather than new plastic. Greenhouse gas emissions are nine times greater than mechanical recycling.

The industry’s response? As of late 2023, 24 U.S. states have passed laws reclassifying chemical recycling facilities as manufacturing rather than waste disposal, reducing regulatory oversight. The industry that told us the power was ours has successfully lobbied to exempt its fake solutions from environmental regulation.

Or consider the recycling symbol itself. Starting in 1989, the plastics industry quietly lobbied almost 40 states to mandate that the triangle of arrows appear on all plastic containers, including plastics they knew couldn’t be economically recycled. Coy Smith, who ran a recycling business in San Diego, watched his bins fill with unrecyclable plastic overnight as consumers saw the symbol and assumed everything was fair game. A 1993 internal industry report admitted the code was “being misused” as a “green marketing tool” creating “unrealistic expectations.”

When recyclers organized a national protest and fought for years to change the symbol, they lost. “We don’t have manpower to compete with this,” Smith told NPR. “It’s pure manipulation of the consumer.”

Or consider deposit-return schemes, one of the most proven interventions for beverage container recycling. Germany, Norway, Denmark, and Finland all achieve over 90% return rates. The mechanism is simple. Yet France, Italy, Belgium, and Spain debated deposit schemes for years without implementation. Why? The Belgian packaging industry saved an estimated €465 million through spending pennies in comparison in lobbying against them. Municipal governments resist “having their material taken away.” Industry groups raise claims of “double taxation.” The opposition isn’t environmental concern; it’s economic interest dressed in public-interest language.

This is what actual environmental villainy looks like. Not theatrical pollution for its own sake, but political operations defending profitable arrangements through legitimate-seeming channels. Captain Planet trained us to watch for barrels being dumped in rivers. We weren’t watching the hearing rooms where deposit-return schemes died, or the state legislatures where “chemical recycling” got reclassified.

Recycling Is Not One Thing

Part of the problem is the word “recycling” itself. It suggests a single process when actually it describes wildly different operations with wildly different success rates. Treating them as equivalent (as the universal recycling symbol does) is part of the misdirection. It implies that consumer virtue is the key variable, when actually the determining factors are material properties, economics, and infrastructure.

Metal recycling succeeds almost everywhere because the economics are favorable. Recycling aluminum uses 95% less energy than primary production. The EU recycles approximately 100 million tonnes of steel annually, with 56% of production from scrap. Recovery rates exceed 95% for building metals, 99% for lead batteries, 90% for aluminum in vehicles.

Paper recycling works where infrastructure exists. Established mill demand for recovered fiber, clear economic value, fibers that can be reused approximately seven times before degrading. 19 European countries achieve recycling rates above 70%.

E-waste presents challenges but responds to policy. The EU achieves a 42.5% recycling rate (the world’s highest) under the WEEE Directive. But 75-80% of global e-waste still ships to Africa and Asia for informal processing.

Glass recycling works technically but economics are marginal. The material is heavy and expensive to transport, while virgin material remains cheap but that is rapidly changing. Silicate that is used in glass (which tends to be high quality) is also used to make chips and tech. So as time goes on, the boom in AI and it’s demand for hardware will increase incentives in recovering materials from both e-waste and glass.

Plastic recycling is not a policy failure. It’s a material science problem. American rates have actually declined, from 9.5% in 2014 to roughly 5-6% by 2021. Over 16,000 chemical and polymer combinations exist; plastic degrades with each recycling cycle; mixed plastics are difficult to separate; many recycled plastics cannot meet food-grade safety standards; virgin plastic remains cheaper than recycled material. Even well-designed policy cannot overcome fundamental physics.

However, there are plastic recycling programs that does work. Deposit-return systems for beverages (which use plastic bottles) achieve 97-99% in Germany, 92.3% in Norway, 93% in Denmark. Lithuania went from under 34% to over 90% after implementing its system in 2016.

State capacity should be redirected toward production limits, material substitution, and narrow targeting of the plastics (PET and HDPE) that can genuinely be recycled.

Sweden sends only 1% of its waste to landfill. Approximately 39% is recycled and 59% is converted to energy through 34 waste-to-energy plants producing 19.5 TWh annually, providing heat to 1.47 million apartments and electricity to 940,000 homes. For genuinely non-recyclable materials, managed thermal treatment beats burial. This requires honesty about what recycling can and cannot achieve, honesty the Captain Planet framing discouraged.

Tokyo takes this further. The city is already famous as one of the most YIMBY places on earth: national zoning laws, permissive building codes, and streamlined approvals have allowed Tokyo to add housing at rates that make American cities look paralyzed. But Tokyo’s YIMBY ethos extends beyond zoning. When you run out of land, you make more (sometimes out of your own trash).

The city operates 19 incineration plants across its 23 central wards, processing millions of tons of waste annually. But the Japanese didn’t stop at energy recovery. The Shinagawa Incineration Plant alone produces 180 tons of bottom ash daily. Rather than landfilling it, engineers melt the ash at 1,200 degrees Celsius and remold it into blocks used to pave pedestrian sidewalks. These blocks also form the foundation of new landfills laid on the ocean bed. Because they’re processed at such high temperatures, they’re pollution-free, more environmentally sound than the construction and domestic waste that built earlier generations of reclaimed land. Since 1592, Tokyo has reclaimed roughly 250 square kilometers from Tokyo Bay, about 15% of the original bay area. The city has turned garbage into a resource that creates another resource: land.

Tokyo Disneyland sits on reclaimed land in Urayasu. So did the 2020 Olympics venues. Odaiba, the waterfront district packed with shopping centers, museums, and hotels, was built on landfill created in the 1960s. This is YIMBY taken to its logical extreme: not just “yes in my backyard,” but “yes, and we’ll build the backyard too.”

What State Capacity in Recycling Actually Looks Like

The contrast between high-performing and low-performing recycling systems is not explained by cultural differences or citizen attitudes. It’s explained by effective state intervention, or the lack of it.

Germany built the global framework beginning in the early 1990s. The 1991 Packaging Ordinance introduced Extended Producer Responsibility: producers and retailers became legally responsible for taking back and recycling the packaging they put into the market. The 1996 Closed Substance Cycle and Waste Management Act extended this principle across entire product lifecycles.

The Green Dot system operationalized EPR by requiring manufacturers to pay licensing fees based on the weight and material composition of their packaging. These fees fund collection and recycling infrastructure. The Pfand deposit system, with its €0.25 deposit on single-use containers, achieves 97-99% return rates.

Taiwan went from “Garbage Island” to recycling leader in two decades. In 1993: only 70% collection coverage, virtually no recycling, two-thirds of landfills at capacity. Today: 55% diversion nationally, 67% in Taipei, daily waste generation fallen from 1.14kg to 0.4kg per capita between 1997 and 2015.

The mechanism: residents must purchase government-approved blue bags for mixed waste, while recyclables can be disposed of in any bag. Pay-as-you-throw creates direct financial incentive for sorting. Combine this with manufacturer fees based on actual collection costs, enforcement through fines and public shaming, and convenient collection (trucks five nights per week, mobile apps tracking locations). The result: a $2.2 billion recycling industry with over 2,000 firms, up from approximately 100 in the 1980s.

Japan’s approach reflects the pressures of a densely populated island nation with severely limited landfill capacity. The Basic Environmental Law (1993) and Fundamental Law for Establishing a Sound Material-Cycle Society (2000) created comprehensive frameworks. Material-specific laws followed: the Container and Packaging Recycling Act, the Home Appliance Recycling Law, Law for the Recycling of End-of-Life Vehicles. Vehicle recycling achieves 92-100% effective recovery rates.

Japan’s Top Runner Program offers a model worth studying. Rather than setting minimum efficiency standards, the government identifies the best-performing product in each category and requires all manufacturers to meet or exceed that level within a specified timeframe. Non-compliant companies face public naming and regulatory sanctions. The approach works because non-compliance has costs. It harnesses competitive dynamics for public benefit.

Norway’s deposit system, operated by non-profit Infinitum, ties environmental taxes on producers to performance: the tax decreases as return rates increase and disappears entirely at 95%. The system achieves less than 1% litter rates. Only 1 in 8 bottles found on Norwegian coasts originates from Norway.

These systems share common features: clear legal frameworks, aligned economic incentives, adequate infrastructure, enforcement with consequences, long-term political commitment. They do not share unusual levels of citizen virtue. Germany recycles because Germany built institutions.

America Can Do This, Just ask the City of Sin

A skeptical reader might object: perhaps Americans simply can’t build this kind of state capacity. Perhaps there’s something about our political culture, our federalism, our individualism that makes German-style intervention impossible here.

Las Vegas proves otherwise.

In 2002, Las Vegas hit an inflection point. The Colorado River experienced its lowest-ever recorded flows. The Southern Nevada Water Authority used more water than it ever had before. Demand outstripped supply in the driest state in the nation. Ninety percent of Vegas’s water comes from Lake Mead, whose elevation has dropped 170 feet since 2000.

The response wasn’t a public awareness campaign asking residents to take shorter showers. It wasn’t a message that “the power is yours.” It was state capacity.

For every square foot of grass homeowners removed and replaced with xeriscaping, they received $3. Through this program, Vegas has pulled out a quarter of the turf grass in the metro area, saving 11 billion gallons annually.

Ninety-nine percent of indoor water is recycled. “Everything we use indoors is recycled. If it hits a drain in Las Vegas, we clean it. We put it back in Lake Mead,” said John Entsminger, SNWA’s general manager. The Bellagio fountain (20 million gallons) operates on a closed-loop system. The water is constantly filtered and reused; it doesn’t hit the sewer.

Water use has declined 48% despite 750,000 new residents moving to the region. The city is targeting 86 gallons per capita by 2035; the national average exceeds 100. “Las Vegas has become a water conservation rock star in recent decades,” said Brian Richter, chief scientist at The Nature Conservancy’s Global Water Program.

Has there been pushback? Of course. “People get emotional about grass,” Kurtis Hyde, maintenance manager at Par 3 Landscape, told the Salt Lake Tribune. But residents largely understand the necessity. “I feel like if I can do my small little part to helping conserve some of our water here in Las Vegas, that I’m doing a small part to help everyone else,” homeowner Linda Laird told Reuters.

She feels she’s doing her part. But that feeling exists within a regulatory structure that made conservation the default and waste the exception. The Bellagio fountain still runs. The casinos still glitter. The Strip uses only 5% of regional water. Las Vegas didn’t ask for virtue and hope for the best. It changed the rules.

“The drought woke us up in 2002 and showed that we needed to do a whole lot more than we were doing,” said JC Davis, director of customer care at Las Vegas Valley Water District. Crisis created political space for intervention. The intervention worked.

If Las Vegas can do this for water, why can’t America do it for recycling? The answer isn’t technical impossibility. It’s political economy.

San Francisco: The Gap Between Knowledge and Action

San Francisco is the American recycling program most often cited as successful. Examining it closely reveals not success but the distance between what’s possible and what American political economy permits.

The achievements are real. The city pioneered mandatory composting in 2009, operates a three-stream collection system (recyclables, compostables, landfill), and has invested in sorting infrastructure for decades. Diversion rates sit in the high 70s to low 80s, roughly double the national average. When China’s 2018 ban hit, San Francisco weathered the shock better than peers: 1.06-1.4% contamination rates, far below Sacramento County’s 25%. The city’s composting operation produces genuinely useful products: Recology claimed that 650 tons of organics collected daily become approximately 350 tons of OMRI-listed, US Compost Council certified compost sold to orchards, vineyards, and organic farmers.

But the metrics are slippery. The celebrated 80% includes construction debris most cities exclude. The SF Public Press reported that 15-19% of blue-bin contents (items San Franciscans carefully sort believing they’ll be recycled) end up landfilled as contaminated residuals. The diversion rate has plateaued for over a decade. The city acknowledged missing its 2020 zero-waste goal and pushed targets to 2030.

More revealing is how the city achieved these results. San Francisco’s recycling operates as a weird pseudo public/private monopoly that’s employee owned. Recology holds exclusive collection rights throughout the city under a 1932 ordinance. Unlike other similar monopolies in other cities run by private corporations like Waste Management, who had a less than stellar reputation with recycling, this structure delivered operational benefits: aligned incentives, long-term infrastructure investment, institutional knowledge accumulated over decades.

But like other monopolies and private utilities, it also delivered corruption. In 2020, the city’s Public Works director was arrested on federal corruption charges; he had accepted bribes from Recology in exchange for rate increases. The company entered a deferred prosecution agreement with the DOJ and paid over $130 million in settlements. Yet the monopoly persisted. Recology outspent anti-monopoly campaigners 55:1 in a 2012 ballot measure. After the scandal, the company ramped up lobbying rather than scaling back. In 2025, the Refuse Rate Board approved a 24% rate increase over three years.

San Francisco’s public utilities (SFPUC for water, sewer, and power) performed well without comparable scandal. The city knows how to keep the city politics from affecting the public utilities (for the most part). A municipal waste authority would preserve operational benefits while eliminating the reducing what bad actors can do to drive corruption. That reform hasn’t happened because the political economy protect this terrible situation.

The gap between San Francisco’s ~80% (inflated, plateaued, corruption-tainted) and Germany’s 97-99% deposit-return rates represents the distance between what American political economy permits and what state capacity can actually achieve.

The Behavioral Evidence

Research on recycling behavior confirms what the policy evidence suggests: economic incentives matter more than moral appeals. A study in the American Economic Review found that economic incentives are particularly influential in promoting recycling, more so than social norms about how neighbors perceive one’s behavior. The effects can be discontinuous, transforming non-recyclers into avid recyclers.

Deposit-return programs outperform both garbage pricing and recycling subsidies. Research on motivation crowdingsuggests pay-as-you-throw systems may actually strengthen intrinsic motivation, while mandatory recycling regulations may weaken it. How policies are framed matters, but structure beats sermons.

Why We Don’t Do What Works

We know what works. Extended Producer Responsibility. Deposit-return schemes with meaningful deposits. Pay-as-you-throw pricing. Investment in domestic processing infrastructure. Honest acknowledgment of what can and cannot be recycled.

Why don’t we do it?

Industry lobbying blocks proven interventions. Existing arrangements benefit incumbents who have resources to defend them. And the Captain Planet framing, much more bigger than the show itself, served as ideological cover for inaction. It directed a generation’s environmental energy toward individual virtue rather than political organizing. It suggested the problem was consumer behavior rather than institutional design. It let us feel good about sorting while the systems that determine outcomes went unbuilt.

The Frontier of Recycling

State capacity isn’t static. Across the world, governments are extending the frameworks that work into new domains.

The EU Packaging and Packaging Waste Regulation will require mandatory deposit-return systems for all member states by 2029, with targets of 77% collection by 2025 and 90% by 2029. Countries like Spain, which currently achieves only ~41% PET bottle collection, must implement systems by 2027.

In developing countries, the frontier includes integrating informal waste pickers (an estimated 15 million people globally) into formal systems. Brazil’s National Solid Waste Policy explicitly calls for inclusion of waste picker cooperatives in municipal contracts. India’s SWaCH cooperative in Pune has negotiated formal agreements with municipal government.

State capacity isn’t a one-time achievement. It evolves. New waste streams emerge; new policy frameworks respond.

Bottomline

The power was never yours. The power is in policy. In legislation. In regulatory design. In state capacity built over decades. In deposit-return schemes and Extended Producer Responsibility and pay-as-you-throw systems. In politicians who write laws and agencies that enforce them and courts that uphold them.

Captain Planet told a generation that individual choices would save the world and “The Power is Yours”. That was wrong. The sorting was never going to be enough. The villains who understood that systems matter better than a show about saving the ecosystem, and they’re still winning.

> But Tokyo’s YIMBY ethos extends beyond zoning. When you run out of land, you make more (sometimes out of your own trash).

San Francisco used to do this too! It's kind of unimaginable in this era of preciousness about wetlands, but SOMA is all terra nova.