Korean Men Are Falling Out of the Marriage Market Faster Than Women

35% of Korean Adults May Never Marry. Three Decades Ago, It Was 5%. Three decades of data show this isn't delay, and economic shocks is making men undateable, not just unmarriageable

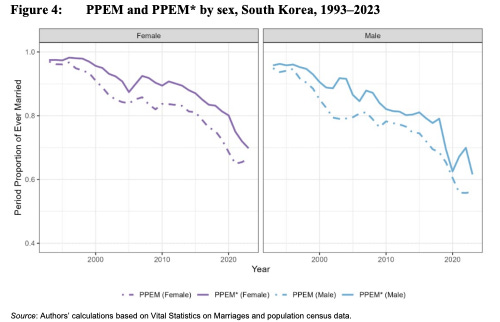

By 2023, only 56% of Korean men were on track to ever marry, compared to 67% of women. Three decades earlier, both figures exceeded 95%. Marriage in Korea hasn’t just declined; it’s become gendered in ways that reveal how economic shocks operates.

Women’s retreat from marriage has been gradual, predictable, almost stately. You could draw the trend line with a ruler. Men’s trajectory is jagged, think sharp drops, partial recoveries, then steeper drops. Between 2019 and 2021 alone, men’s marriage rates collapsed nearly ten percentage points.

Sam Hyun Yoo’s new study in Demographic Research allows us to distinguish between “later” and “never.” For Korea, the answer is increasingly “never.”

It isn’t that men aren’t doing enough chores, Korean men been increasing their share of household chores. It is just that mechanism isn’t just about marriage. Economic shocks and instability, in spite of economic growth, makes young people, especially men, undateable before it makes them unmarriageable. This isn’t just about Korea.

The Numbers

Marriage rates have collapsed over three decades. Among women, the total first marriage rate fell from 0.83 in 1993 to 0.49 in 2023. Among men, it fell from 0.80 to 0.46. The period proportion ever married dropped from 97% to 67% for women and from 95% to 56% for men. Mean age at first marriage rose six years for women (from 25.2 to 31.2) and five and a half years for men (from 28.3 to 33.8).

The critical distinction lies in comparing adjusted and unadjusted measures. For women, timing-adjusted and unadjusted measures track almost identically, indicating structural retreat. For men, timing effects are larger and the measures diverge, indicating both postponement and structural retreat, plus greater volatility.

The pandemic revealed underlying dynamics that had been partially obscured. Marriage rates hit their lowest point in 2021. International marriages involving Korean grooms collapsed when borders closed. Male mean age at marriage temporarily stopped rising. The reason wasn’t that young men started marrying; older grooms, typically those in international marriages, had simply disappeared from the data.

Structural Retreat, Not Just Delay

The conventional story about declining marriage goes like this: people are marrying later, but they’ll get there eventually. Fertility rates look alarming, but they’re distorted by timing. Once postponed marriages and births occur, the picture will normalize.

We think this story is importantly wrong, at least for Korea.

The evidence comes from comparing two measures: the period proportion ever married (PPEM) and its tempo-adjusted counterpart (PPEM*). The technical details matter less than what the comparison reveals. PPEM tells us what share of a synthetic cohort would ever marry under current marriage rates. PPEM* adjusts for the distortion created when everyone delays marriage simultaneously, a distortion that makes period rates look artificially low during postponement phases.

If Korea’s marriage decline were primarily about timing, we’d expect a substantial gap between these measures. PPEM would fall, but PPEM* would hold relatively steady, revealing that underlying marriage propensity remained intact beneath the timing shifts.

That’s not what the data show.

For women, PPEM and PPEM* have declined in near-parallel since 1993. The gap between them, typically 2 to 6 percentage points, is modest and stable. Korean women aren’t just marrying later. They’re opting out. The decline in period rates reflects genuine behavioral change, not statistical artifact.

Men’s patterns differ. The PPEM-PPEM* gap is larger and more variable, indicating stronger timing effects. But both measures have still declined substantially. Men are postponing and retreating. Their rates also jump around more from year to year.

What looked like delay has revealed itself as decline. The transition from near-universal marriage to a society where a third or more may never marry represents genuine structural transformation, not a timing artifact waiting to correct.

The Male Volatility Problem

Here’s something the aggregate numbers obscure: Korean women’s retreat from marriage has been gradual, predictable, almost stately in its decline. The trend line slopes steadily downward with minimal year-to-year variation. You could practically draw it with a ruler.

Men’s trajectory looks nothing like this. It’s jagged. Sharp drops, partial recoveries, then steeper drops. Between 2019 and 2021, men’s PPEM plummeted from 65% to 56%, a collapse of nearly ten percentage points in two years. Women’s decline over the same period was significant but far smoother.

Why are men more volatile?

Start with international marriages. Korean men, particularly those in rural areas or with limited economic prospects, became increasingly reliant on foreign brides starting in the mid-2000s. Women from Vietnam, China, and the Philippines provided an alternative for men who struggled in the domestic marriage market. When COVID-19 closed borders in 2020, that channel shut overnight. Male marriage rates didn’t just decline. They collapsed.

Economic precarity hits men’s marriageability harder too. Korea’s marriage market, like marriage markets everywhere, prices male economic stability at a premium. When economic conditions deteriorate, men don’t just delay marriage. They fall out of the eligible pool. The 1997-98 Asian Financial Crisis shows up in the data as a sharp marriage rate drop for both sexes, but men’s recovery was slower and weaker.

The technical structure of male marriage timing also amplifies shocks. Men marry later than women on average and across a wider age range. When the composition of who marries shifts (fewer international grooms one year, fewer younger domestic grooms the next) male period indicators swing more sharply. Women’s more concentrated marriage timing creates stability; men’s dispersal creates exposure.

The 2020 pandemic offers a natural experiment. That year, something unusual appeared in the data: men’s adjusted and unadjusted marriage rates suddenly converged. The reason wasn’t that men stopped postponing marriage. The type of man getting married had changed overnight. With international marriages gone, the remaining grooms were younger and domestic. And there were far fewer of them. The male mean age at first marriage, which had been rising steadily for decades, temporarily plateaued.

If you want to understand where marriage is heading, watch the men. Their rates are more exposed to economic and institutional shocks, more sensitive to cross-border dynamics. By 2023, men’s PPEM stood at 56%, compared with 67% for women.

The Partnership Threshold

The marriageability problem is real, but framing it as a marriage problem understates the damage. Economic precarity doesn’t just prevent wedding ceremonies. Just to be cliche, let me point out that it prevents relationships from forming in the first place.

Consider the evidence from the United States, where we have richer data on partnership and dating. Partnership rates among young adults have fallen steadily, and cohabitation hasn’t backfilled the decline. General Social Survey data show the share of men under 30 reporting no sexual partners in the past year rose from around 10% in 2008 to nearly 30% by 2018. Dating apps show stark asymmetries: Hinge’s internal data suggest the top 10% of men receive the majority of female “likes,” while a large share of men receive almost none. These patterns predate the pandemic by years.

The mechanism operates at the dating stage, not just when couples consider commitment.

Let me ask you a question. Why does no one want to date a gig worker? Relationships require planning. Even casual dating involves coordination: schedules, shared activities, splitting costs. A partner whose work hours shift based on algorithmic demand, whose income fluctuates from $1,000 to $6,000 monthly (theoretical high), is difficult to date. The logistical friction compounds before anyone’s thinking about marriage.

Economic instability also signals other instabilities. Fair or not, gig work reads as unsettledness. Someone driving for a rideshare app at 34 prompts questions: Why doesn’t he have a regular job? What’s the plan? Is something wrong? These judgments may be uncharitable. Plenty of gig workers are capable people navigating a labor market that offers them little else. But the judgments operate in dating markets regardless. Gig work is an extreme (and increasingly common) example, but you get the gist.

Valerie Oppenheimer identified the key dynamic in her 1988 work on marriage timing: marriage markets don’t just require male income, they require signal clarity about future economic trajectories. Stable employment at modest wages sends a clearer signal than the theoretical gig work averaging higher earnings with massive variance. (Side note: In real life, gig workers earn low earnings while keeping the massive variance.) A teacher earning a predictable salary is more legible as a partner than a freelancer whose monthly income swings between feast and famine. The variance matters as much as the mean.

This legibility problem doesn’t require long-term planning to matter. Even early-stage dating involves implicit assessment: Is this person’s life together? Can I picture a future here? Income variance and schedule chaos make those assessments harder. Uncertainty is unattractive at every relationship stage.

The effects compound. Men priced out of the dating market don’t gain experience or build confidence. Meanwhile, stably employed men become relatively more attractive, concentrating attention on a narrowing pool. The dynamics feed on themselves.

Institutional Variation, Universal Mechanism

We want to be careful here. The marriageability threshold operates across every developed economy. What varies is how different institutional configurations mediate its effects, and what becomes visible as a result.

In societies where cohabitation has become normalized (Scandinavia, France, increasingly the United States), couples priced out of marriage frequently cohabit instead. Partnership still forms; it takes a different legal shape. The marriageability threshold affects marriage rates, but its impact on partnership formation and fertility is partially buffered. Partially: partnership rates are falling in these countries too, not just marriage rates.

In societies where cohabitation remains uncommon (Korea, Japan, Taiwan, parts of Southern Europe), the same threshold operates differently. When marriage becomes inaccessible, there’s no alternative partnership form to absorb the pressure. Men who can’t clear the bar don’t cohabit; they remain unpartnered. Nonmarital births don’t rise to compensate; they remain rare. In Korea, under 5% of births occur outside marriage. On that note, nonmarital births are falling in the west, so that buffer is evaporating.

This institutional difference doesn’t make one configuration more or less functional. But it does affect what the data reveal. Korean marriage statistics capture partnership decline more directly than Western marriage statistics do. The TFMR and PPEM indicators aren’t just measuring willingness to formalize a relationship legally. They’re measuring union formation itself.

The underlying mechanism is the same everywhere: economic instability makes people less attractive as partners. The institutional channeling determines where the effects become most visible. Korean data offer unusual clarity on dynamics that are harder to isolate in high-cohabitation societies, because there’s less statistical noise from alternative partnership forms.

What This Means

Fertility policy that ignores the marriage market is incomplete. Korea has invested heavily in childcare subsidies, parental leave, and other policies aimed at reducing the costs of childrearing. These matter. But if the binding constraint is increasingly partnership formation, if people aren’t reaching the stage where fertility decisions become relevant, then downstream policies will have limited effect. The bottleneck is earlier in the pipeline.

Labor market policy is family policy. The connection between employment precarity and relationship formation isn’t just a Korean phenomenon. It operates in Chicago, Berlin, and Tokyo alike. Societies that tolerate high levels of unemployment, gig work, contract employment, and income volatility among young adults are implicitly accepting the relationship-market consequences. Those consequences are now visible in the data.

Male outcomes deserve specific attention. We’re accustomed to analyzing gender gaps in ways that focus on women’s disadvantages, and those disadvantages are real. But on partnership formation, men are increasingly the ones falling behind. Men’s marriage rates are lower and more volatile. Men’s dating market outcomes show starker inequality. A policy conversation that treats “family formation” as gender-neutral will miss where the constraints are tightening fastest.

The international marriage dynamic warrants scrutiny. For roughly a decade, international marriages provided a release valve for Korean men priced out of the domestic marriage market. When that valve closed in 2020, the underlying dysfunction became visible. This suggests the domestic marriage market had already failed for a significant share of men. International marriages just made the failure less statistically apparent. As those flows resume unevenly, the data will become harder to interpret, but the underlying domestic dynamics haven’t changed.

We don’t know whether Korean marriage rates will stabilize at current levels, decline further, or partially recover. What we can say is that three decades of data show no sign of a floor. Each cohort has married at lower rates than the last. The modest rebound in 2022-2023 appears to reflect postponed pandemic marriages being realized, not a genuine reversal. The structural transformation continues.

The point

The optimistic interpretation of falling marriage rates, that people are just delaying, has become difficult to sustain. In Korea, where unusually clean data allow us to distinguish timing from structure, the answer is now clear: this is structural retreat. People aren’t marrying later. They’re not marrying.

The dynamics are gendered. Women’s decline has been steady and predictable. Men’s decline has been steeper and more volatile, buffeted by economic shocks and migration policy. Men’s partnership rates are lower and falling faster.

The mechanism isn’t unique to Korea. Economic precarity makes people unmarriageable; more than that, it makes them undateable. The marriageability threshold operates in every developed economy. What varies is the institutional context that channels its effects and determines what becomes visible in aggregate statistics.

Korea’s marriage data offer a window onto dynamics that are harder to see elsewhere, because its institutional structure produces unusually clear signals. The gig economy, housing costs, and employment instability don’t just delay family formation. They prevent it. That’s the lesson from three decades of Korean marriage data, and there’s no reason to think it applies only there.

A growing share of people in developed economies, disproportionately men, are not forming the partnerships that previous generations took for granted. Whether that’s a problem depends on your values. That it’s happening is no longer in doubt.

"Korea has invested heavily in childcare subsidies, parental leave, and other policies"

Have they? Do they spend 10% of GDP on them?

I agree that boosting the take home pay of married men is the trick to increasing fertility, but I don't see anyone coughing up the money for it.

Great look at a natural experiment that lets us tease out something important.

QQ - what's driving the divergence between Korean M and F marriage rates? Korean women-but-not-men are still getting internationally married? Serial monogamy marriage, where one man marries two different women over a time period?