America vs. Singapore: You Can’t Save Your Way out of Economic Shocks

Saving regret has less to do with procrastination than we thought, and more to do with whether your country absorbs economic shocks or lets them hit your savings

Key Facts

Procrastination does not meaningfully predict saving regret. Across 12 psychometric measures tested in both countries, the relationship is weak to nonexistent, and where statistically significant, it frequently runs in the opposite direction from what the behavioral economics literature predicts.

Economic shocks do. Exposure to negative financial shocks is the dominant predictor of wishing you’d saved more.

About half of Americans between 60 and 74 wish they had saved more. That’s a familiar finding, and it comes with a familiar explanation: people procrastinate. They know they should save, they intend to save, and then they don’t, because the present is vivid and retirement is abstract, because inertia is powerful, because human beings are not the rational optimizers of the textbook. A generation of behavioral economics has crystallized around this idea. We get nudges, automatic enrollment in 401(k) plans, default escalation schedules. The policy apparatus assumes, at bottom, that under-saving is a self-control problem.

A new working paper from Rohwedder, Hurd, and Börsch-Supan suggests we’ve been looking in the wrong place. The authors surveyed thousands of people aged 60–74 in the United States and Singapore, two countries that both emphasize individual responsibility for retirement but differ sharply in institutional design. They asked a simple question: if you could do it over, would you have saved more? Then they tested what actually predicts the answer. Is it procrastination? Or is it something else?

The something else turns out to be economic shocks. And the difference is not subtle. Which is (depends on you, darkly or not so) funny, considering what a lot of people are saying about LLMs/AI/etc and the job market.

What do you mean by “tested.”

The authors didn’t just ask people whether they procrastinate and whether they regret their saving. They fielded 12 separate psychometric measures: questions about putting off tasks, giving up when things get difficult, settling for mediocre results, losing motivation, preferring immediate gratification. These are the kinds of instruments the behavioral literature treats as markers of present bias and poor self-control. The prediction, grounded in decades of work from Laibson, Thaler, O’Donoghue, Rabin, and others, is straightforward: people who score high on procrastination should be more likely to wish they’d saved more.

They aren’t. Across both countries, across 21 separate statistical comparisons per dataset, the relationship between procrastination and saving regret is, to a first approximation, nonexistent. Where significant associations do appear, they frequently run in the wrong direction. In Singapore, people who report never putting off difficult things are more likely to express saving regret than those who sometimes do. The authors later confirmed these null results using a different, widely validated procrastination scale. The finding held.

Now consider the alternative explanation. The surveys also asked respondents whether they had experienced negative financial shocks over their lifetimes: unemployment spells, large health expenses, earnings shortfalls, divorces, early forced retirement. Here the pattern is immediate and powerful. In the U.S., 69 percent of respondents reported at least one negative shock, compared with 46 percent in Singapore. And among Americans who experienced such shocks, 61 percent expressed saving regret, compared with 42 percent among those who didn’t.

Four of the five most common negative shocks are labor-market related, and the U.S. leads on every one. Some 18 percent of American respondents reported an unemployment spell serious enough to damage their finances, compared with 11 percent in Singapore. Among those who experienced that shock, 62 percent of Americans expressed saving regret versus 54 percent of Singaporeans. The pattern repeats across the board: health limiting work (20 percent of Americans, 14 percent of Singaporeans), earnings falling short of expectations (16 percent versus 12 percent), being pushed into early retirement (13 percent versus 8 percent). In each case, the shock is both more common in the U.S. and more financially scarring.

It’s not just that more Americans lose their jobs. It’s that losing a job in America does more lasting damage to a household’s financial trajectory. An unemployment spell in the U.S. leaves people staring at their retirement accounts with a 62 percent chance of wishing they’d saved more. The same event in Singapore produces regret at 54 percent, still painful, but meaningfully less so. Multiply that differential across every category of labor market disruption, across decades of working life, and you begin to see why the two countries diverge so sharply on saving regret despite similar levels of individual responsibility.

As the number of negative shocks accumulates, regret in the U.S. climbs steadily, reaching 76 percent among those who experienced five or more. In Singapore, regret barely budges: it hovers around 50 percent regardless of how many shocks a person reports. And among respondents in both countries who experienced no negative shocks, the rate of saving regret is nearly identical: 42 percent in the U.S. versus 40 percent in Singapore. The cross-national gap in regret is almost entirely a gap in shock exposure and shock consequences.

Why does the same job loss hurt more in America?

This is where institutional design enters the story, and where the comparison gets interesting, because Singapore’s advantage isn’t just about retirement accounts. (What follows draws on the paper’s detailed institutional background as well as more recent developments.)

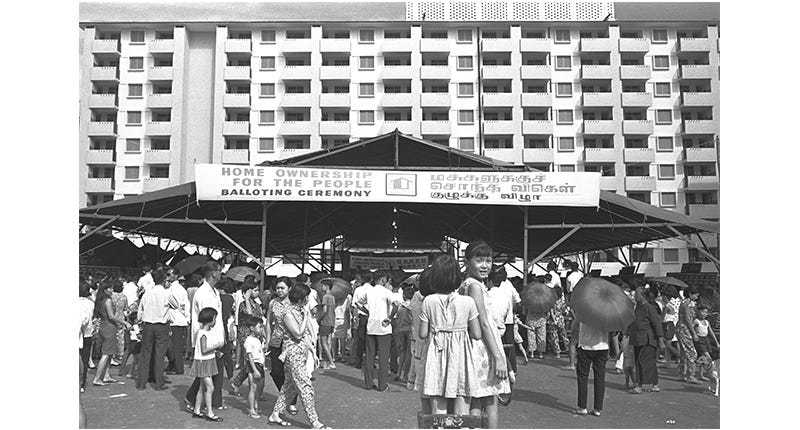

Singapore’s Central Provident Fund mandates that roughly 37 percent of earnings flow into individual accounts earmarked for retirement, housing, and health care. These aren’t optional. They aren’t nudges. They’re compulsory contributions, split across three accounts: an Ordinary Account for housing and eventually retirement, a Special Account locked until age 55 for retirement only, and a MediSave Account for health insurance and medical expenses. The system doesn’t pool risk the way Social Security does, but it creates a buffer. When a health shock hits, there’s a dedicated account to absorb it. When housing costs are high, there’s a dedicated account for that, too. And critically, these accounts exist before the shock arrives. They aren’t savings that a job loss can redirect toward rent.

On the labor market side, Singapore takes a different approach, though not always a generous one. For most of its modern history, there was no government-provided unemployment insurance at all. The stated policy aim was re-employment, not income replacement. The Retirement and Re-employment Act, introduced in 2007 and enacted in 2012, requires employers to offer contract extensions to workers reaching the retirement age (initially 62, now 63), with penalties for unjustified refusals. The re-employment age has been raised repeatedly, to 67 in 2017, to 68 in 2022. The results are visible in the data: labor force participation among Singaporean men aged 60–64 rose from 53 percent in 2005 to 77 percent in 2019. For women in that age range, it jumped from 21 percent to 51 percent. Singapore doesn’t primarily cushion job loss with cash benefits. It tries to prevent job loss from happening in the first place, or at least to shorten the gap.

That said (and this postdates the paper’s data collection), Singapore has recently acknowledged the limits of this approach. In April 2025, the government launched the SkillsFuture Jobseeker Support scheme, which provides up to S$6,000 over six months to involuntarily unemployed citizens earning S$5,000 or less per month. The payments taper over time and are tied to active participation in job search activities, career coaching, and training. The government set aside more than S$200 million for the program, expecting roughly 60,000 eligible individuals per year. It’s modest by international standards, but it represents a significant shift in a country that had long resisted anything resembling unemployment benefits, and it’s paired with structured re-employment support rather than offered as a standalone cash transfer.

Now consider the American alternative. The U.S. unemployment insurance system is, to put it plainly, a mess. And the mess is measurable. In 2024, only 27 percent of jobless workers nationwide received UI benefits. That’s not a typo. Roughly three out of four unemployed Americans get nothing. State-level variation is staggering: Minnesota led the nation at 55 percent; Kentucky managed 10 percent. The duration of benefits ranges from as few as 12 weeks in North Carolina, Florida, and Tennessee to 26 weeks in most states, and the maximum weekly benefit varies from $235 in Mississippi to $823 in Massachusetts.

A 55-year-old American worker who loses her job faces a gauntlet of compounding risks that her Singaporean counterpart largely does not. She may or may not qualify for unemployment benefits depending on which state she lives in, how she lost her job, and whether she can navigate the application process. If she does qualify, the benefits may last as few as 12 weeks. If her employer provided her health insurance, as is the case for the majority of covered workers, she loses that too, precisely when stress and disruption make health problems more likely. Employer-provided health insurance tied to employment means that a job loss can simultaneously eliminate income and health coverage, a compounding shock that Singapore’s system avoids by design. Roughly 42% of American workers lack access to employer-sponsored retirement plans in the first place. And when shocks arrive, a layoff at 55, a medical crisis, a divorce, they erode whatever savings a household has managed to accumulate.

The health care comparison is particularly stark. Health spending shocks occur at roughly equal rates in both countries, around 10 to 11 percent of respondents in each sample reported a large medical expense. But the consequences diverge dramatically. In the U.S., experiencing a health spending shock is associated with a 24-percentage-point increase in saving regret relative to those with no negative shocks at all. In Singapore, the corresponding increase is just 10 points. Same shock, radically different financial scar, because in Singapore, MediSave and subsidized public insurance absorb much of the blow. It helps that Singapore spends roughly 4 percent of GDP on health care; the U.S. spends 17 percent.

Does this mean nudges are useless?

No? Automatic enrollment works. Default escalation schedules increase contributions. The behavioral economics toolkit has real value, but these are tools at the end of the day, not a cure all. If the reason people end up with less savings than they’d like is primarily that life happened to them, job losses, health crises, family disruptions, stagnant wages, then making it marginally easier to contribute to a 401(k) treats a symptom rather than the disease.

And the disease is uninsured risk. The paper reframes under-saving not as a failure of willpower but as a failure of risk management, or more precisely, as a failure to provide the institutional infrastructure that lets households manage risk. Singapore’s system is far from perfect. It concentrates wealth heavily in housing (median housing wealth of about $377,000 against median total wealth of $575,000 for older Singaporeans), leaving less available for non-housing consumption. It lacks the redistributive features that make Social Security critical for lower-income Americans. And even with all that forced saving, 45 percent of older Singaporeans still wish they’d saved more. Mandatory contributions are not a complete answer.

But they are a better starting point than assuming the problem is procrastination. The evidence here is fairly clear: when you compare people who weren’t hit by shocks, Americans and Singaporeans look almost identical in their saving satisfaction. The gap opens up because Americans face more shocks, more severe shocks, and weaker institutional buffers against those shocks. College costs in the U.S. doubled in real terms between 1989 and 2016 while median wages stagnated. Divorce rates are higher. Labor market disruptions are more common and more financially devastating. Each of these is a rock thrown at the household balance sheet, and no amount of commitment-device wizardry prevents the damage.

There’s one more finding worth highlighting.

The authors discovered that probability numeracy, the ability to reason about uncertainty and likelihood, was strongly associated with lower saving regret in both countries. Individuals who answered all probability questions correctly had saving regret rates 14 percentage points lower in the U.S. and 19 points lower in Singapore. Financial literacy, by contrast, showed no consistent relationship.

That distinction matters. Financial literacy is about understanding compound interest and inflation. Probability numeracy is about understanding risk, that bad things happen with some frequency, that the future is uncertain, that planning means preparing for contingencies. If the core problem is shock exposure rather than procrastination, it makes sense that the skill most protective against regret is the one that helps people think clearly about an uncertain world.

The policy implications follow naturally, and the paper is explicit about them. Strengthening social insurance against catastrophic risks, health expenses, long-term care costs, labor market disruptions, would do more to reduce saving regret than yet another tweak to choice architecture. Expanding access to retirement savings vehicles matters, certainly, but so does ensuring that a single medical bill or job loss doesn’t wipe out decades of careful accumulation. The authors point to buffer-stock saving programs, emergency savings accounts, and integrated health-and-retirement saving frameworks as directions worth pursuing, while noting that self-insurance alone is “inefficient protection against large shocks because of the lack of risk-pooling” and “insufficient because many persons cannot save enough to meet all contingencies.”

We’ve spent a generation treating under-saving as a problem of human psychology. The better framing might be simpler and, in its way, harder: people aren’t failing to save because they’re weak. They’re failing to save because the world is rough, and their institutions don’t do enough to help them weather it.

FAQs

What else predicts lower regret (besides avoiding shocks)

Probability numeracy stands out. Respondents who answered all probability questions correctly had saving regret 14 percentage points lower in the U.S. and 19 points lower in Singapore. Financial literacy, the “Big Three” questions on compound interest, inflation, and diversification, showed no consistent relationship. In Singapore, lower financial literacy was actually associated with lower regret. The distinction: financial literacy measures whether you understand how money grows; probability numeracy measures whether you understand that bad things happen and can reason about how likely they are.

A long financial planning horizon (10+ years) was associated with roughly 10 points lower regret in the U.S. and 6 points in Singapore. Higher wealth also reduces regret, particularly in the U.S., where the gap between the highest and lowest wealth quartiles is about 24 percentage points (36% vs. 60% regret). In Singapore, the gradient is flatter (40% vs. 46%).

Shock accumulation: the numbers behind the dose-response pattern

Some 23 percent of Americans reported three or more shocks; only 10 percent of Singaporeans did. U.S. regret climbs steeply with accumulation: 42 percent with zero shocks, 54 percent with one, 61 percent with two, 76 percent with five or more. In Singapore, regret rises to about 50 percent after one shock and then barely moves, hovering between 48 and 55 percent regardless of additional shocks.

Divorce and college costs

Divorce: 19 percent of U.S. respondents experienced divorce or separation (63% regret); only 1.5 percent of Singaporeans did (40% regret).

College costs: 9 percent of Americans reported higher-than-expected college expenses (67% regret) versus 4 percent of Singaporeans (46% regret). Context from the paper: U.S. college costs doubled in real terms between 1989 and 2016 while median wages stagnated; Singapore university tuition rose only 14 percent between 2007 and 2016 while median wages rose 23 percent.

“Positive” shocks are messier than they look

Several ostensibly positive shocks (working longer than expected, receiving financial help from family, spending less than expected) turn out to correlate with negative shocks. In Singapore, 61 percent of those who worked longer than expected had also experienced a negative shock, compared with 43 percent of those who hadn't. In the U.S. the pattern is similar if less stark: 80 percent versus 67 percent.

These "positive" events may reflect coping with adversity rather than genuine windfalls: working longer because you had to, receiving family help because a health crisis demanded it. The authors exclude them from their summary positive-shock variable, and are candid about why: "defining unambiguous positive shocks is challenging." Even after that exclusion, the cleaned-up variable behaves oddly. In the U.S., experiencing a positive shock is associated with about 9 percentage points lower regret. In Singapore, it has virtually no effect.

Measuring regret: framing and correction

About 54 percent of Americans aged 60–74 wish they’d saved more, compared with 45 percent of Singaporeans. Very few in either country wish they’d saved less (1.5 percent and 4.3 percent respectively). These figures are after a built-in correction: respondents were reminded that saving more means spending less, then asked which categories of spending they could have cut. Those who said “no way we could have cut spending” were recoded as not expressing regret. Before that correction, regret was 66 percent in the U.S. and 53 percent in Singapore. The survey also ran a framing experiment: asking “spend less and save more” versus just “save more” reduced regret by about 7 percentage points.

How the study was designed

The U.S. data come from the RAND American Life Panel (ALP), an Internet-based panel of about 6,000 individuals, surveyed in two waves (2016 and 2017–18; 2,618 respondents aged 60–74, with 2,111 overlapping both waves). The Singapore data come from the Singapore Life Panel (SLP), a monthly Internet-based survey representative of the Singapore population aged 50–70 at recruitment, fielded in May 2018 (4,309 respondents aged 60–74). The SLP questionnaire was designed to match the second ALP wave as closely as possible. Descriptive statistics are weighted; regressions are unweighted. Standard errors in ALP regressions are adjusted for repeated observations from overlap cases.

To be extremely unfair to Americans, we suffer like this by ideological preference. Our country constantly votes, except during natural disasters, to move tail risks from institutions (state, quasi-state, *and* private-sector corporate) to households.