2/5 - Why economic (especially energy) shocks permanently lower fertility rates & total maternal rates (TMR)?

We still feeling the impact of the 70s Oil Crisis and the Great Recession today

Japan's economy roared back in the 1980s. The Nikkei hit record highs, unemployment vanished, and corporate profits soared. Yet something unprecedented happened: both fertility and motherhood rates, which had fallen during the 1973 oil crisis, never recovered.

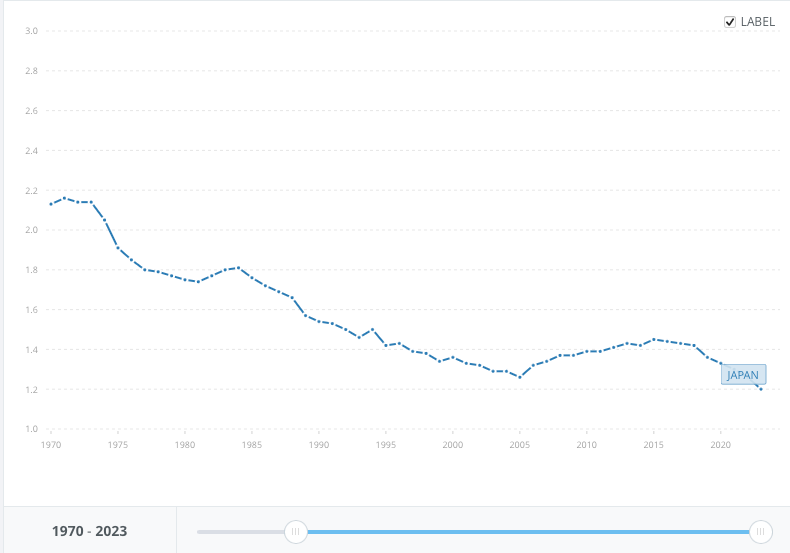

Japan's total fertility rate of 2.1 in 1973 fell to 1.7 before the bubble, briefly picked up for one year, then went into free fall until 2005. The rates kept falling through the boom, through the bust, through the recovery. By 2022, only 58.7% of Japanese women were becoming mothers, down from over 95% in the 1960s.

Note: This is a second article in the series:

This pattern pops up again with eerie precision. By 2015, America had fully recovered from the 2008 financial crisis. Unemployment hit historic lows, the stock market reached record highs, and wages finally started rising. Yet marriages and first births remained at crisis levels. Shaw's paper shed light on the hidden collapse: while total fertility rate showed modest decline from 2.1 to 1.8, motherhood rates crashed from 76.1% to 69.4% and never bounced back.

This defied everything economists knew. In the 1970s, they feared overpopulation as economies recovered. Recessions had always caused temporary fertility delays and young couples waited for stability, then had children when times improved. The baby boom followed the Depression. Mini-booms followed every recession since World War II.

Generation X, not the Baby Boomers, achieved the highest fertility rates of living generations with 2.0-2.1 children in the 1990s and 2000s. Yet suddenly, Millennials and Gen Z have lower birth rates than not just Gen X, but even the Boomers during the Great Stagflation of the 1970s and 1980s.

The Failed Explanations

Cultural Change? The Data Says No

Despite claims from multiple biased parties, Americans still want 2.6 children—virtually unchanged since polling began. More than 90% of adults either have children, want children, or wish they had children. Only 5% don't want children at all, the same percentage as in 1990. Among childless adults over 50, only 38% say there was never a time when they wanted children.

Women's Careers? The Timing Doesn't Match

Female employment rose steadily from the 1960s until the 2000s, yet fertility remained stable until specific shock points: October 1973 and September 2008. The gradual became sudden at precise moments, always following economic crises by exactly 12 months. Recent research increasingly confirms that women who earn more money are actually more likely to have children.

Dating Apps? Too Late to Explain the Collapse

Marriage rates were already collapsing before Tinder launched in 2012. Besides the 1970s oil shock, the most recent decline started in 2009, almost exactly 12 months after Lehman Brothers collapsed. Too precise for technological explanation, too sudden for cultural shift.

The 47 Prefecture Impossibility

The oil shocks' impact on marriage and birth rates defies coincidence. In 1974, exactly 12 months after the oil crisis, all 47 Japanese prefectures—from metropolitan Tokyo to rural Hokkaido to subtropical Okinawa; experienced simultaneous motherhood decline according to Shaw's paper. The probability: less than 0.0001, equivalent to flipping heads 47 consecutive times.

Monthly birth data revealed precise timing: breakpoints began clustering in October 1974, peaked in November, and continued into early 1975. Accounting for the typical 12-month conception-to-birth timeline, this aligns exactly with when Japanese media coverage of the "Oil Shock" peaked on October 19, 1973.

The same pattern appeared globally. Italy's motherhood rate, above 95% through the 1960s, began its steepest historical decline in 1974. The UK showed identical timing. The US started earlier with stagflation in 1971 but followed the same trajectory. Always the same lag: 12 months from economic shock to demographic collapse.

The Permanent Scar

Ryota Mugiyama's research in Japan reveals the devastating mechanics behind why recovery never comes. Economic shocks force men into unstable or temporary jobs. Men in temporary employment are 3 percentage points less likely to marry each year compared to those with regular jobs. Unemployed men face a 5.5 percentage point annual penalty. These effects compound devastatingly: by age 30, employment instability explains 31% of never-married men and 45% of childless men.

But here's what makes it permanent; the "scarring effect." Even men who eventually secure stable employment never fully recover their marriage & fertility prospects. Each additional year in regular employment increases marriage probability by only 0.2 percentage points. A man scarred by five years of instability needs 15 additional years of stable work to match the marriage prospects of his immediately-employed peers. By then, he's 45 competing for the same romantic opportunities as stable 30-year-olds.

This occupational scarring extends across developed economies. Julia Hellstrand's Finnish research shows that between 2010-2019, male fertility crashed from 1.73 to 1.21, with decline varying enormously by economic security:

ICT workers: -41% fertility

Environmental scientists: -42%

Chemical engineers: -40%

Police officers: -9% fertility

Agricultural workers: -20%

Teachers: -29%

The pattern transcends Nordic welfare states. Melbourne Institute research comparing Australia and Germany shows how different forms of temporary work create lasting fertility penalties across institutional contexts. Australian female casual workers show a 29.5% reduced likelihood of having their first child compared to permanent workers. German women on fixed-term contracts face a 22.3% reduction, and those without formal contracts see their chances plummet by nearly 48%.

The Automation Factor

The scarring effect now extends beyond traditional economic shocks. Haiyang Lu's research shows that automation correlates with reduced job stability, creating similar damage as economic shocks. Industrial robot exposure reduced fertility by 9.4% overall, with manufacturing workers experiencing 27.7% decline through multiple pathways: monthly wages fell 4.3%, working hours increased, and marriage likelihood decreased.

Strikingly, robot exposure reduced the ideal number of children by 6.3%, suggesting automation's effects extend beyond immediate economic impacts to reshape family aspirations themselves. By 2020, China had 246 robots per 10,000 manufacturing workers, double the global average. Between 2010-2020, Chinese women's childlessness tripled to 5.16%.

The Death of the Marriage Market

Over 90% of unmarried Japanese women still consider male earning potential important for marriage. Despite dual-earner rhetoric, the expectation persists that male earnings should exceed female earnings, especially after children arrive.

This pattern extends far beyond Japan's borders. Studies across 24 countries using data from 1.8 million online daters confirm that women universally prioritize men's resource-acquisition ability, with this preference being nearly 2.5 times stronger than men's preferences for female earning capacity. Even highly educated American women continue to prefer higher-earning husbands, with the tendency for women to marry men with higher incomes persisting despite women's educational advances. Chinese online dating research reveals that women specifically prefer men who have higher incomes than themselves, with higher-income male profiles receiving 10 times more visits than lower-income ones.

The marriage market math operates identically across cultures. Research comparing Chinese and South Korean mate preferences shows that Chinese women rate "earning capacity/potential" as more important than men do, while Korean women prioritize "wealthy" and "social level." Australian research confirms that 90% of women prefer men who earned their money over those who inherited it, prioritizing earning capacity over static wealth.

Even as American marriages become more egalitarian, with 16% of wives now primary breadwinners, about 48% of married men still prefer to earn more than their wives. A European meta-analysis covering 27 countries demonstrates that employment instability creates lasting fertility penalties, with men's unemployment being particularly detrimental and women's fixed-term contracts creating the strongest negative effects. The pattern is "more severe in Southern European countries, where social protection for families and the unemployed is least generous."

You cannot simply "culture" people into accepting different norms. It does not work; it has not worked. People can and should have the marriage aspirations they want, and whoever wants to be the homemaker should, regardless of gender.

In an upcoming article, we will discuss how there is a positive correlation between a woman's career success and fertility rates. It's not an "either/or" proposition—it's about dealing with what people actually want.

Since 2008 and COVID, damage to the job market for young people has reached the point where young men with college degrees experience unemployment levels similar to high school graduates. This instability has started to reach healthcare and teaching, so it won't be long before till women-dominated professions see similar impacts.

The Marriage Revelation

Shaw isn't the first to notice this pattern. Lyman Stone has made this argument for years. In an IFS blog post, he documented that 75% of the total fertility decline since 2007 is attributable to the shifting likelihood that people are married, not married couples having fewer children, but simply fewer marriages.

In the 2020s, unmarried women were "extremely unlikely to have a first birth, whereas for married women without children, there was about a 15% probability of having children in the next year." Marriage is the crumbling bridge to motherhood, and that bridge has collapsed.

Americans are marrying at 27-29 instead of 25, and this delay alone creates a collapse in first births. Every year of delay compounds, women who would have had three children starting at 25 might have one starting at 30.

The achievability gap wasn't always so large. From 1990 to 2007, the fertility gap was consistently just one-third as large. The widening coincides with Shaw's documented total motherhood rate collapse following 2008.

The Bottom Line

It's unambiguous: economic shocks create permanent damage through marriage market collapse. People (both men and women) scarred by early-career instability are far less likely to achieve their family dreams. A 35-year-old with newfound stability competes against 27-year-olds who never experienced disruption.

This explains why birth rates never rebound after modern recessions. Whether 1973 or 2008, the pattern repeats: economic shock → marriage collapse → permanent birth rate decline.

Like it or not, preventing economic and energy shocks is pronatalist policy. Every financial crisis, every automation wave without transition support, every period of instability creates virtually irreversible damage. The 1970s oil shocks still echo in today's missing births.

Stop asking "why aren't people having children?" Ask "why aren't people achieving job stability and getting married?" The answer: both stable employment (the prerequisite for marriage) and marriage itself are becoming luxury goods.

Energy supply and price stability are pronatalist policy. Job growth and stability are pronatalist policy. Employment protections are pronatalist policy. Even if we achieve the right policies and stop future shocks in their tracks, full recovery will take time.

Like it or not, this is the reality most policy makers try to ignore.

Spittin' fire! I love how you cross correlated the specific drops by career, the drop in motherhood in toto in terms of percent of women becoming mothers, and things like recessions and automation both measurably contributing.

I've never seen this collection of facts all aggregated before, but it paints a really clear and compelling picture, kudos for putting that together.

Oh, I just saw this

I think culture is the dominant factor, measuring that through "desire" for kids alone isn't the best

People may "want" the same number of kids, but they seem to perceive more "barriers" too

"Standards" for the life that should be given to kids, and the education that they have to go through, changed, this is partly cultural, and with it fertility is affected

Also, I probably pointed this out before, but ....money helps with fertility, while employment for women doesn't

If two women are working same hours and one of them is earning more, the higher earning woman isn't necessarily harming her ability to have kids compared to the other woman

But, working in itself, (taking money out of the equation) probably harms fertility for women

So, it is a combinations of feeling financially secure, and not working much